ONE HEALTH QUALITATIVE AND MIXED METHODS

4.12

History of transdisciplinarity

In the video of the previous step we saw that transdisciplinarity research is often done in iterative processes and corkscrew-like research and action strategies. Without a doubt this accounts for the uncertainty of knowledge one deals with, particularly at the beginning of a programme about a real-world problem.

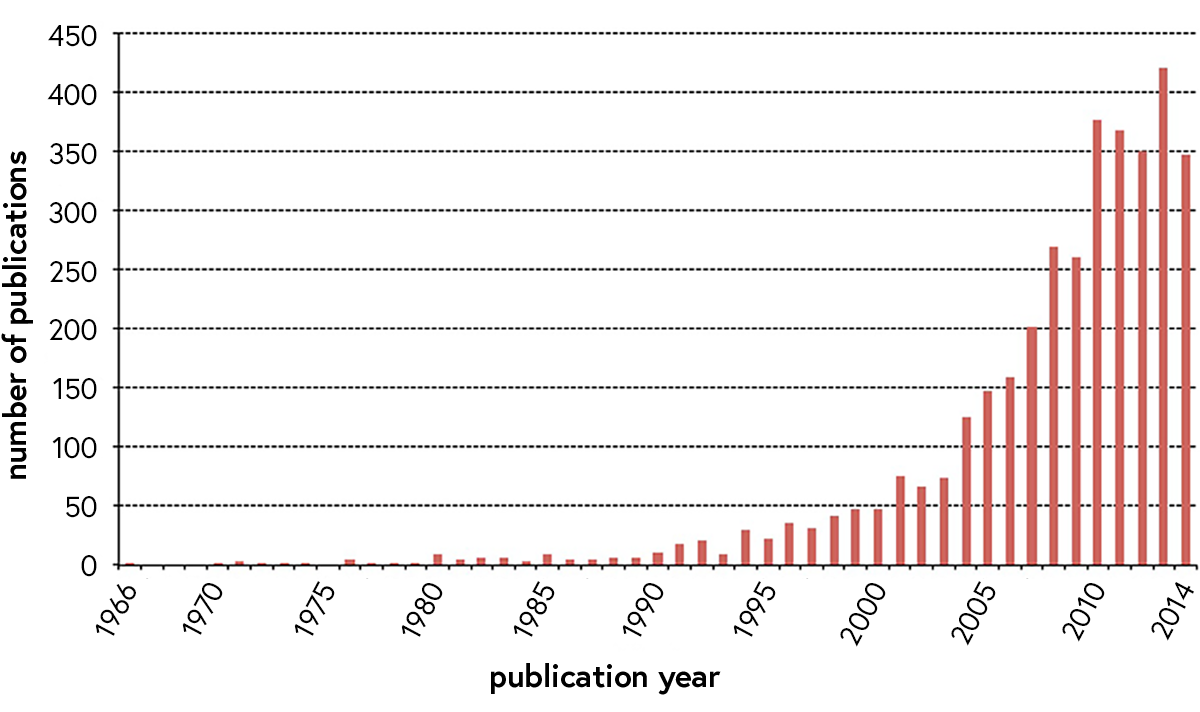

You can see the increasing number of publications on transdisciplinary research over the past half century in the graph below.

Number of publications on transdisciplinary or transdisciplinarity. Search of January 16, 2015 on www.transdisciplinarity.ch.

© www.transdisciplinarity.ch

Pohl et Hirsch Hadorn (2007) have summarised key characteristics and principles of transdisciplinarity as:

-

Collaboration between disciplinary researchers and actors of the life-world.

-

Contribution to substantial knowledge about the issue (practical experience, scientific models, results) and approaches (eg action research).

-

Having a starting point that is not a specific disciplinary paradigm, but a socially relevant problem (eg, violence, hunger, poverty, disease, health, environmental pollution).

Transdisciplinary research is shaped by various lines of thinking and has a variety of definitions. Analogous approaches to transdisciplinarity are post-normal sciences; Science of Team Science in North America, Integration and Implementation Sciences in Australia and Public Engagement in Europe and elsewhere. They all recognise the need to integrate disciplines, engage civil society and acknowledge that a policy question is related to complexity and uncertainty.

In Europe, major events leading to transdisciplinarity as described by the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences were:

-

Observations as the only source of knowledge (concept of ‘positivism’).

-

Dissociation of natural science from philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries. Natural sciences concerned with empirical laws and experimental settings.

-

The emergence, in the 19th century, of the science of society (sociology). It developed the hermeneutic paradigm to understand cultural ideals and assign a meaning to social and cultural phenomena. While natural sciences searched for explanation, sociology searched for meaning, namely during the social crises of capitalism, of urbanisation or of secularisation, when practical solutions were needed.

-

Increasing fear that progressive fragmentation of the sciences could no longer explain complex situations or recognise emerging phenomena. This led to the development of systems theory studies and of multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary thinking.

-

In the second half of the 20th century, rapid population growth led to natural resource crises and to the complex of interactions of a ‘risk society’. A perception was fostered of the major risk that specialisation cannot recognise possible negative side effects for modern civilisation. The civil society, the private sector and public agencies also need to be engaged in research.

-

Social sciences and humanities became involved in activities such as technology assessment and ethical committees on morally sensitive technologies.

-

Mittelstrass (1992) defines transdisciplinarity as a form of research that transcends disciplinary boundaries to address and solve problems related to the life-world. Through scientists entering into dialogue and mutual learning with societal stakeholders, science becomes part of societal processes, contributing explicit and negotiable values and norms in society and science, and attributing meaning to knowledge for societal problem-solving.

References

Hirsch Hadorn, G. et al. (2008). The Emergence of Transdisciplinarity as a Form of Research, in: Hirsch Hadorn, G. et al. (Eds.). Handbook of Transdisciplinary Research, Heidelberg, Springer, 19-39.

Mittelstrass J. (1992). Auf dem Weg zur Transdisziplinarität, GAIA, 1(5): 250.

License

University of Basel