ONE HEALTH QUALITATIVE AND MIXED METHODS

4.3

Understanding what people say, believe, think and do

Zoonoses such as anthrax, brucellosis and bovine tuberculosis (bTB) can be prominent health problems among pastoralist groups, such as the Fulbe, in the Sahelian region. These diseases affect their own health and their livestock which are the main source of their income.

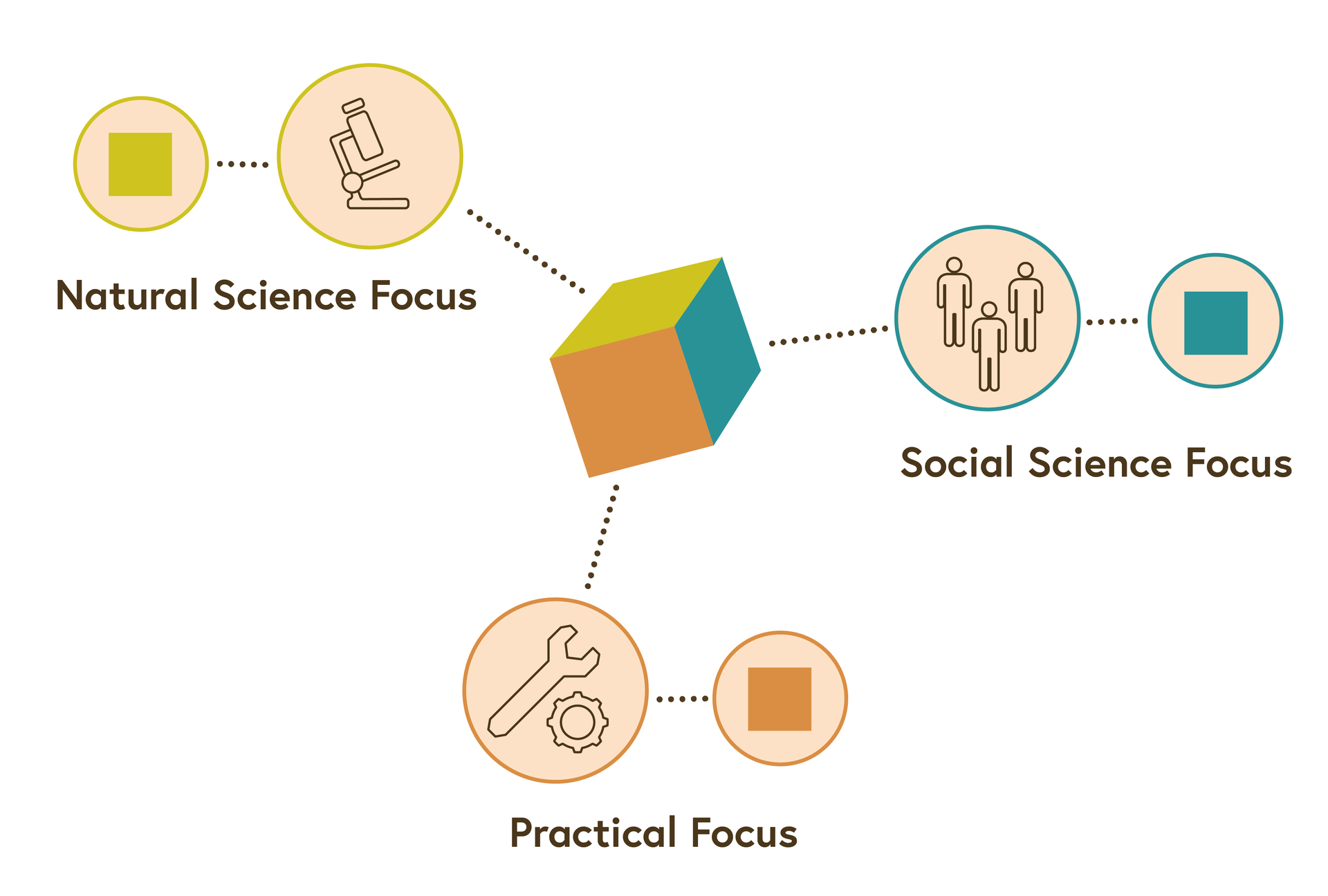

From a biomedical point of view, living closely together with livestock and consuming potentially contaminated animal-source food increases the risk of exposure to different transmission routes of zoonotic pathogens. However, the biomedical view only shows us one side of the cube. We see a green square.

Combining different perspectives

© University of Basel

So far, little is known about the social contexts in which anthrax, brucellosis and bTB occur. How do Fulbe pastoralists explain or conceptualise illnesses that are transmissible from animal to humans? Do they perceive a risk of transmission? How does their health seeking behaviour look when faced with an illness incident?

A study on illness perceptions and health-seeking behaviour of Fulbe pastoralists in Chad found that the pastoralists did not have an illness concept for zoonotic diseases and that they characterised diseases either as animal or human diseases. There was no observable concept corresponding to the biomedical notion of a ‘zoonosis’. By using qualitative methods, the study found that among Fulbe, very few illnesses, for example anthrax, were perceived to be transmissible from animals to humans.The symptoms of the three zoonoses, anthrax, brucellosis and bTB, were considered as a disease burden for animals rather than for humans since they were seen as causing suffering and mortality in livestock rather than in humans. One informant noted ‘the risk of animals making us sick is minor since we live in close proximity and are still alive.’

A recent ethnoveterinary study in Northern Cameroon showed similar findings. The names and descriptions of causes, symptoms, and modes of transmission for anthrax, brucellosis and bTB were different in people and in livestock. When looking at the illness perceptions of the Fulbe pastoralists, other health problems, such as dankanoma (helminth/trichuriasis infection/haemorrhoids) and memri/peowri (rheumatic diseases) were much more prominent for them.

Ideas about the importance of a health problem have an impact on the health seeking behaviour. They belong to the emic, or the internal perceptional, perspective. This perspective is in contrast to the external observational perspective, in our case the biomedical perspective, which we call etic. Adopting the emic perspective, we see another side of the cube: a blue square. You will learn more about the emic and etic perspectives in an upcoming step.

A geographer may look at correlations between alkaline pH of soils and anthrax outbreaks and find a correlation. This is again another perspective. Or, the veterinary services have knowledge on how to most effectively reach mobile pastoralists for livestock vaccination against anthrax. A practical input would then suggest that pastoralists’ livestock can be best vaccinated in a period when they do not yet move long distances before the rainy season where livestock is prone to get infected in these zones. From a practical perspective, they see the orange square instead of the cube.

Only when the three perspectives – emic, etic and practical – are combined can one see that the different squares belong to a cube. One also can think of it as a triangulation of a problem.

Try to formulate a One Health question and describe how you might design a study that possibly includes the three perspectives of context, biomedicine and find an entry point of action.

References

The following article is in German with an English summary: Krönke, F. (2004). Hilfesuchverhalten und die Barrieren der Nutzung des öffentlichen Gesundheitswesens bei pastoralnomadischen FulBe im Tschad, in: Anthropos 99, 25-38.

Moritz, M. et al. (2013). On Not Knowing Zoonotic Diseases: Pastoralists’ Ethnoveterinary Knowledge in the Far North Region of Cameroon, Human Organization 72(1), 1-11.

License

University of Basel