'FROM SOUND TO INK' – EARLY FORMS OF MUSICAL NOTATION

2.2

Visualising music?

We learn to read and write in our childhood. With more or less difficulty we have acquired a cultural technique that we call writing. But it seems that after having learned to read and write we forgot the conceptual basic principles behind these skills quite soon.

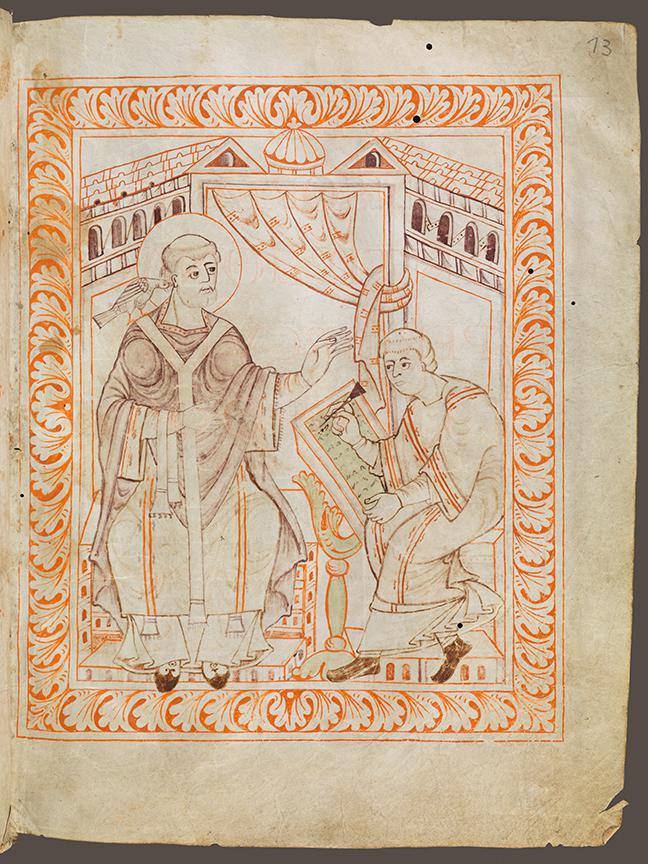

In the medieval iconography the Holy Spirit is represented by a dove and inspires Pope Gregory I as he ‘invents’ the liturgical (Gregorian) chant. A scribe writes the melodies down.

© St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 390, p. 13

www.e-codices.unifr.ch

When we read we usually don’t think about the visual logic of the alphabetical signs, and it is probably even necessary to forget about it in order to understand what we are reading. This functional aspect of writing applies to musical notation as well. Thus, the traditional way of studying notation has always been focused on the problem of deciphering and reading the signs. In that sense, notation is conceived as a pragmatic system aimed at musical performance.

Jacques Derrida’s philosophy of writing, along with the interdisciplinary studies in Visual Culture, enabled a new perspective on notations. The history of musical notation can now be studied as the development of a cultural technique of visualization; notation turns out to be an intriguing semiotic system.

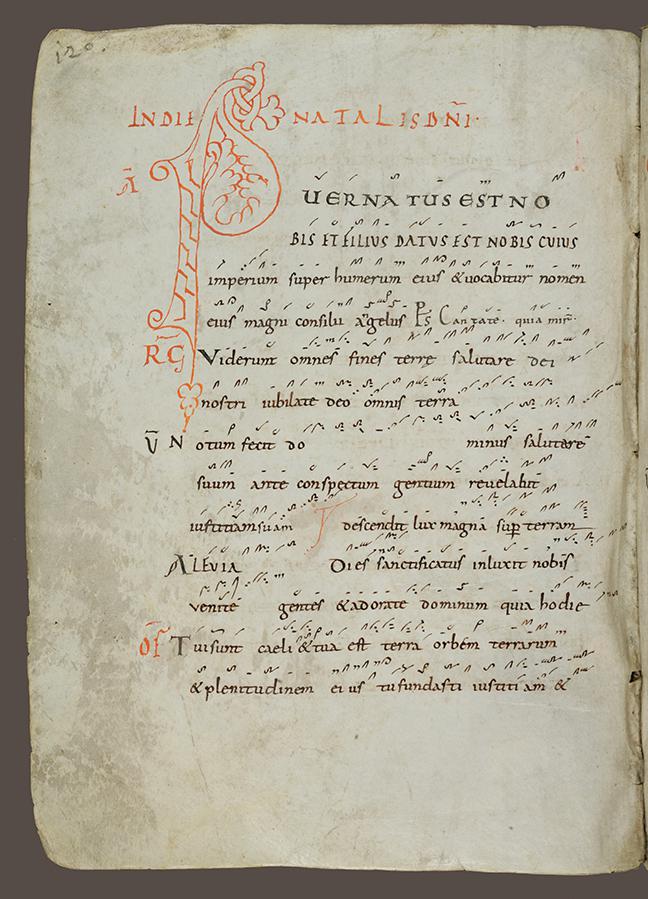

The beginning of the Christmas Mass in a manuscript from the 10th–11th century.

© St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. 342, p. 120

www.e-codices.unifr.ch

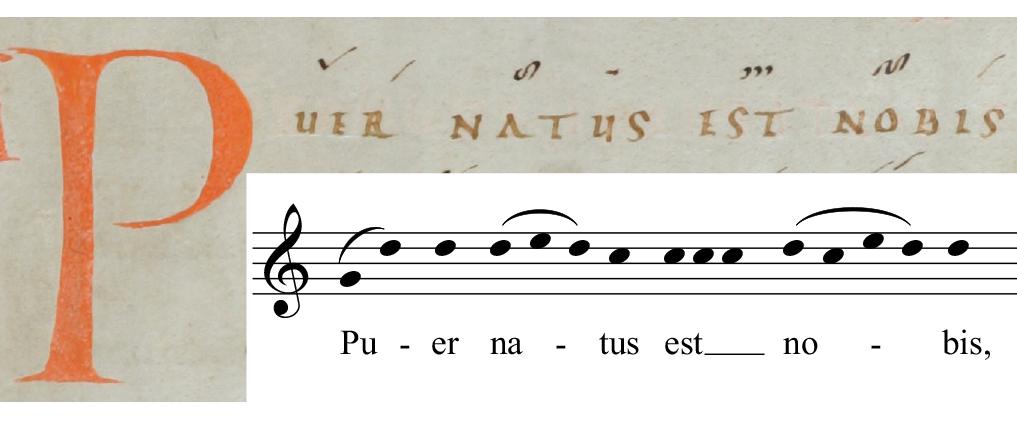

Early medieval notation, for instance, appears as a highly sophisticated system of encoding sound into visual signs. If we take a look at the beginning of musical notation in medieval Europe the following question arises: How did neumes, the earliest notation of plainchant, visualise orally transmitted melodies? In the second half of the 9th century Carolingian singers found it necessary to mark their song texts with little strokes and dots in order to optimise the correct transmission of the repertoire. These little signs are called adiastematic neumes because they do not note the pitches and intervals on staff lines, but represent visually the shape and gesture of the melody. Therefore, it is mere impossible to sight-sing these kind of neumes without having listened to the melody beforehand. These little strokes and dots become musical notation only after the singer has learned the melody orally, that is by hearing it from another singer. Neumes in fact stand for melodic details which help the singer to verify if he or she is singing correctly. This kind of notation did not replace the practice of singing by heart, but helped the singer to recall to memory a huge repertoire of liturgical chant.

In general, we can say that the visual and gestural representation of the melody by adiastematic neumes is based on the following two criteria of visualization:

The relative distinction between high and low.

Neumes can represent the direction of the pitch movement. The first neume, a so-called pes, iconically indicates that the voice rises from low to high. The exact pitches, however, are not represented in this kind of notation.

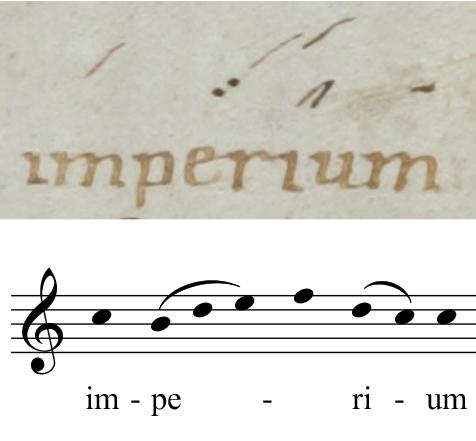

The alternation between single neumes and groups of neumes.

Single neumes are used for single syllables in the text, while melismatic passages are represented by groups of neumes. Here you can witness the alternation between these two elements on the word ‘imperium’.

The different grouping of notes indicate that the performance should be differentiated in terms of voice articulation. When we examine notation beyond its readability, we consider it as a system of visual markers which can generate new semantic connections and create new contexts within the image or the inscribed surface. This means placing an emphasis on the value of notation as a visual medium in order to understand the visual quality of written signs as an inherent and most relevant part of their semantic aspect.

License

Copyright: University of Basel