EARLY MENSURAL NOTATION

4.9

Preparing a transcription

Transcribing music from the past can have different aims. It can be done for practical reasons as it facilitates the reading of a piece for musicians not fluent in medieval notation. It may also be done for the sake of theoretical gain, as it enables us for instance to study and analyse an ancient composition.

In this step you will get an introduction to the basics of transcribing early mensural notation from the late 13th century.

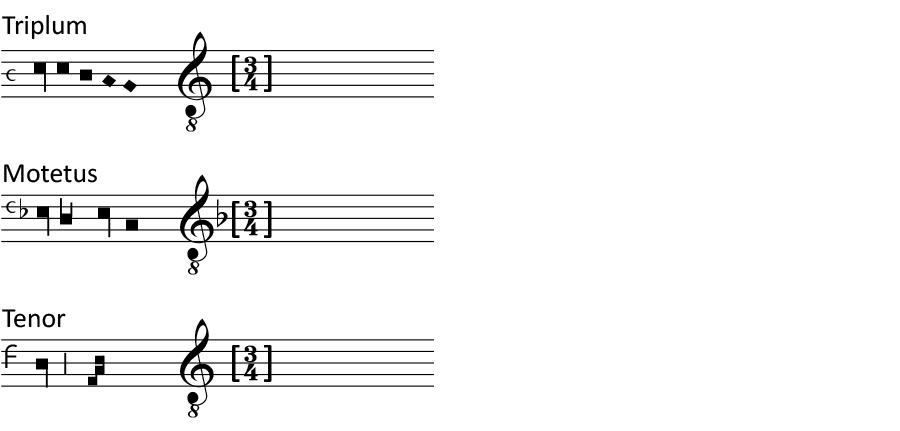

The beginning of the Three-voices Ars Antiqua Motet Amours mi font souffrir / En mai, quant rose est florie / Flos filius eius.

© Montpellier, Bibliothèque interuniversitaire, Section Médecine, H 196, fol. fol.153v–154r

Earlier you learned about some principles of transcribing medieval music. Expanding those, discover some further practical hints:

The first step is to identify the different voices of the polyphonic composition. In this case it is important to realise that the staff line at the top belongs to the end of the previous piece. On the left-hand side you find the triplum (with the initial ‘A’); on the right-hand side, the motetus (with the initial ‘E’) and at the bottom the tenor, introduced by the illuminated letter ‘F’. After identifying the voices, take a five-line staff paper, copy the incipits and draw a line through the staff. Insert the modern clefs considering the range of the original voices (in this example we had to put octave-transposing clefs).

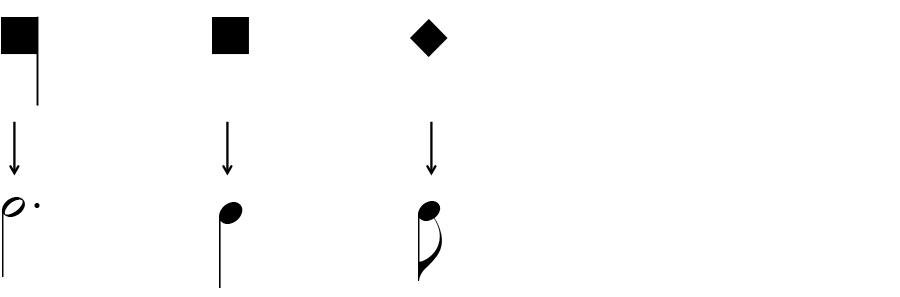

In Ars Antiqua music rhythm is always ternary, so you can easily assume a three-four time, as this music is conventionally transcribed. This means that a longa will be transcribed as a dotted minim (half-note), a brevis as a crotchet (quarter-note) and a semi-brevis as a quaver (eighth-note).

Please note that if there are three consecutive semi-breves, they will be transcribed as a triplet. Of course, if a longa is imperfected by a brevis, the longa will be transcribed as a non-dotted minim (half-note). And if a brevis is altered, it will become a minim (half-note) as well.

A transcription should always fulfil certain scientific requirements: it is important that the core aspects of the original manuscript are always recognisable in your transcription. Sometimes there is the necessity to correct errors or add further information. In that case all modifications or additions should be indicated.

If you delve deeper into the notation of a music manuscript you might come upon the following difficulties:

1. Early music uses C- and F-clefs and not the modern G-clef.

2. In some circumstances musicians of earlier times knew that they had to add flats or sharps to observe certain ‘unwritten’ rules, although these accidentals do not occur in the manuscript.

3. Medieval polyphonic music did not make use of bar lines. The different voices are in most of the cases not written one above each other as we are used to today.

4. Early music often uses signs or notational techniques that a modern score cannot display.

For these problems, the following solutions may be helpful:

1. The use of a so-called incipit: you start your transcription with a copy of the very beginning of the original. This incipit indicates the position of the clef, the existence or non-existence of accidentals and the original note values. Once you have given this information to the reader in the incipit, you can decide which modern equivalent note value suits your purpose better. For instance in the Ars Antiqua repertoire it is common to transcribe the original longa with the modern note value of a minim (half-note). It is also important to indicate the source from which you are transcribing.

2. If you decide to indicate a flat or a sharp on a particular note you have to put it above the note in question.

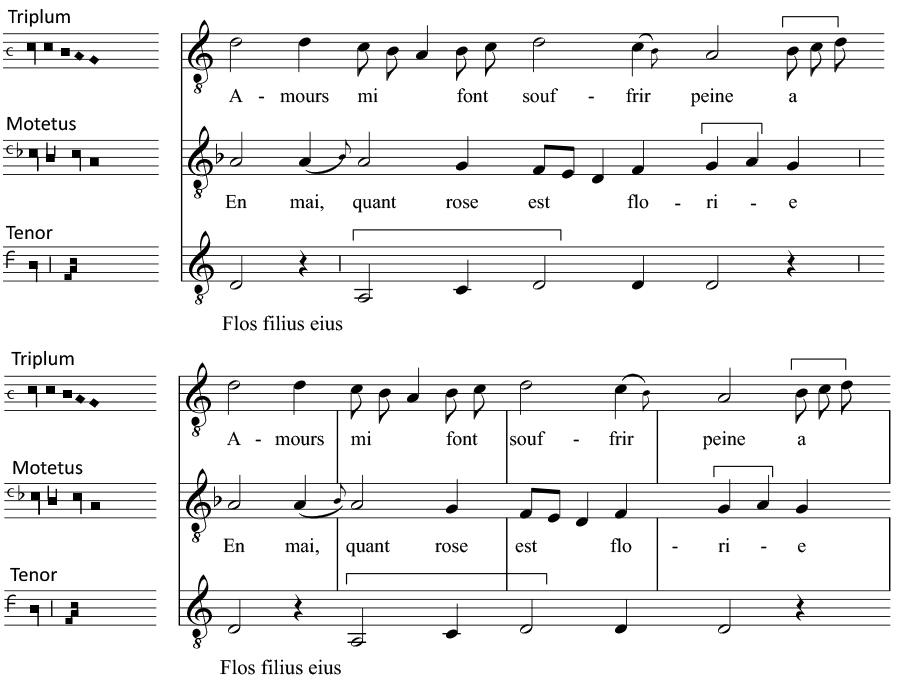

3. In the Ars Antiqua the voices may be placed next to each other. It is useful to transcribe these voices into a single score. Rhythm in medieval music is not confined to closed beat structures that distinguish between stressed and unstressed metrical units (as for example in a waltz); medieval and renaissance music is based on a quantitative concept of time division. The use of bar lines drawn through the staff can therefore lead to misunderstandings. Thus you can realize a transcription completely without any bar lines respecting the original visual structure of the notation. As it may be difficult to follow the rhythm without any bars, you can add bar lines between the staffs following a kind of three-four time.

4. To indicate ligatures it is common nowadays to connect the notes in question with a bracket. In the music of the Ars Antiqua the so-called plicae are still in use. Today it is common to transcribe them with a smaller note slurred to the main note.

After finishing your preparations, you can start your transcription. As you have discovered previously: always start with the lower voice and then add the upper voices one after the other. After having reached the end of the tenor check whether it is correct, so that you have a solid foundation upon which you can build a successful transcription.

Now you are ready to start!

License

Copyright: University of Basel