'FROM SOUND TO INK' – EARLY FORMS OF MUSICAL NOTATION

2.10

Lines and staff

Read, how notation evolved in the 11th century from adiastematic neumes towards staff-notation.

Neumes can be subdivided into adiastematic neumes (not indicating exact pitches) and diastematic neumes (indicating exact pitches). If the adiastematic neumes on the one hand cannot visualise a melody with its intervals and pitches, they outline on the other hand different aspects of musical interpretation, as for instance the voice articulation and the rhythmic feature (due to the addition of episem and with help of the litterae significativae) or the particular vocal sound (as in the case of liquescent neumes).

With the introduction of diastematic neumes, starting from the second quarter of the 10th century, the visualisation of intervals and pitches enabled the singer to learn a melody direct by reading it from the manuscript. During the first decades of the 11th century Guido of Arezzo will talk about this evolution in the history of notation as an important invention.

In French manuscripts with Aquitanian neumes from the 10th and 11th century (see table of neumes) the notational signs are represented by discrete points that are arranged in the space above the text. These neumes are displayed around an axis that permits a quite precise orientation in the pitch range. The respective line was sometimes drawn with ink. In some manuscripts, however, it arises to not more than a dry-pointed line scratched into the parchment (as you may clearly see in the digitalised source linked here). With the help of lines, which indicated the central note of a melody, for example its final note (the so-called finalis), one could draw conclusions regarding the interval-structure of the entire melody.

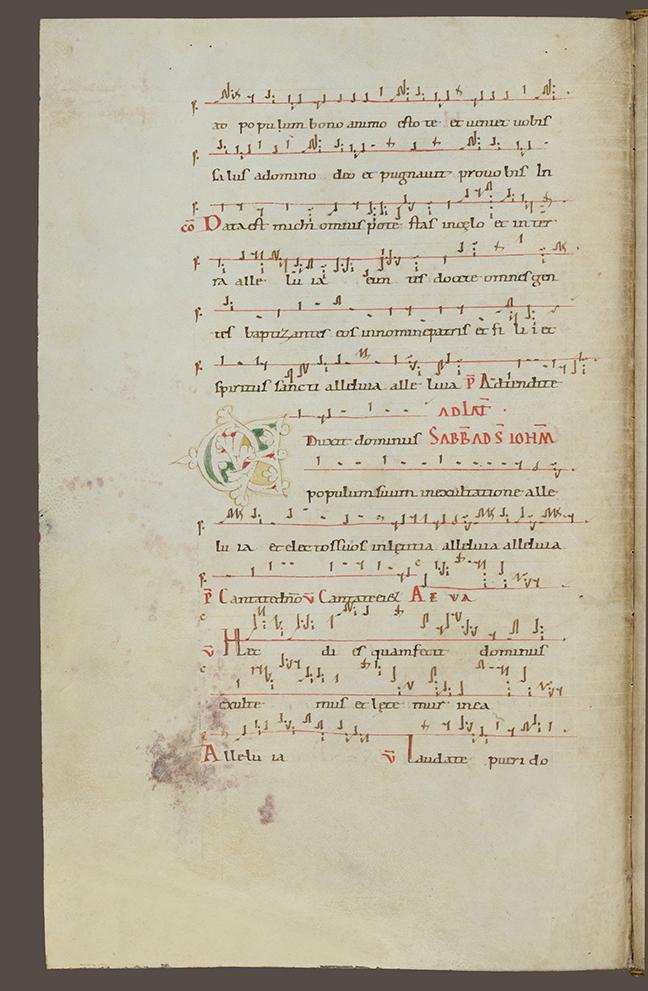

In order to improve the recognition of pitches and to facilitate the identification of the semi-tones, two coloured lines were used in Italian manuscripts from the 11th century: a red one to indicate the F and a yellow one to indicate the C as both notes are above a semi-tone.

Image 1: Roman manuscript (1071) with neumes on lines. The red F-lines are clearly visible. The yellow C-lines are faded because of age. You find them at the bottom of the manuscript between the last F-line and the red A of Alleluia: Search for the two little C’s on the left border.

© Cologny, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cod. Bodmer 74, fol. 86v

www.e-codices.unifr.ch

In addition to that, Latin letters were placed as clefs in order to determine the pitch. Guido of Arezzo (c. 991–1033) claimed, that he had invented this system. A system, notabene, that was further specified as a third line was introduced between the lines of F and C and a fourth drawn above these three lines. Thus the four resulting lines are stacked to express intervallic distances. They permitted to display a fully diastematic notation.

Have a look at this example here of the Christmas introitus Puer natus est from the Gradual of Klosterneuburg.

Manuscripts

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 1240 (10th century).

Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Lat. 776; Lat. 903 and Lat. 1139 (11th century).

Cologny, Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cod. Bodmer 74 (11th century).

Modena, Duomo, Archivio Capitolare, O.I.13 (11th – 12th centuries).

License

Copyright: University of Basel