EARLY MENSURAL NOTATION

4.7

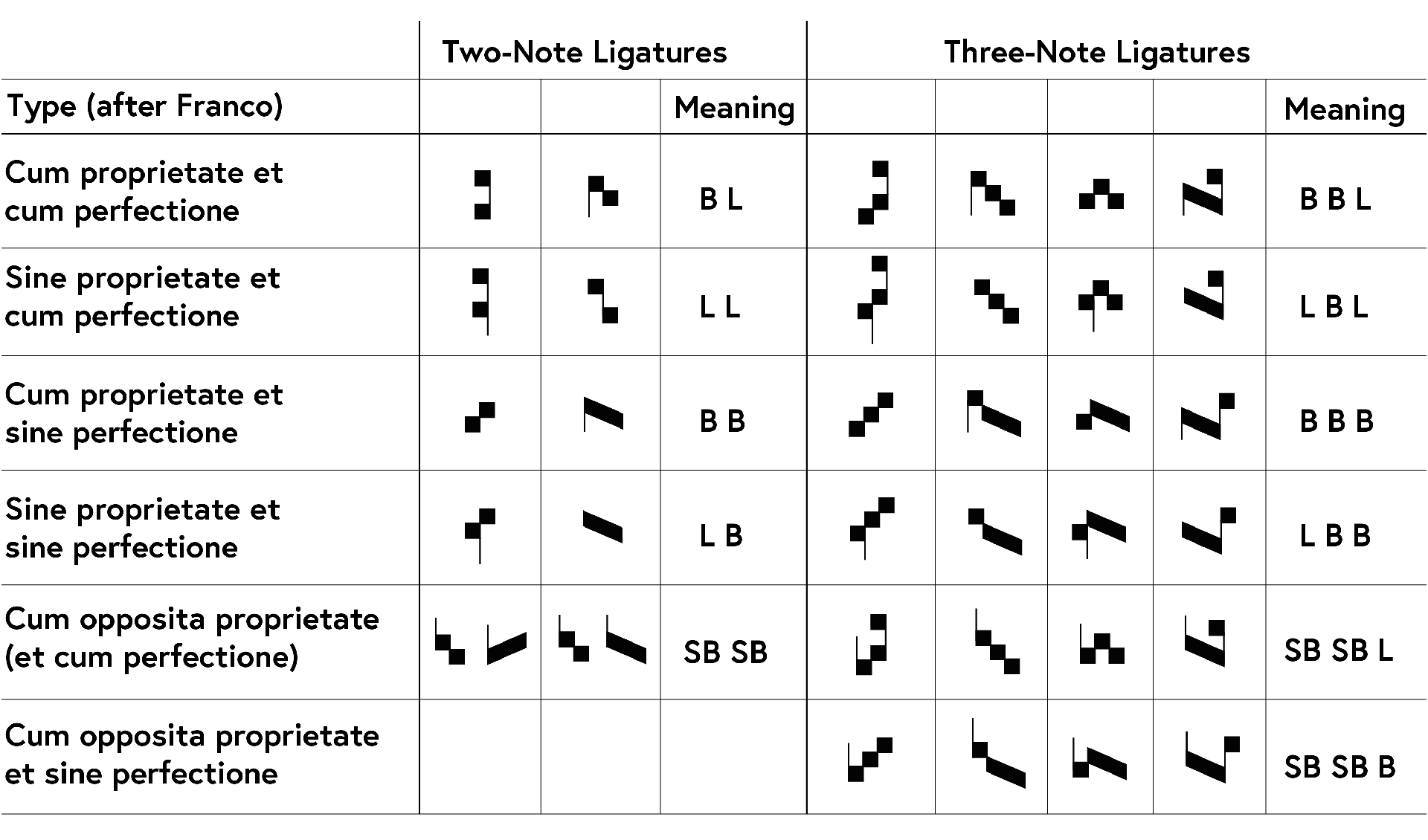

The ligatures by Franco of Cologne: mensural rules II

With the notational reforms of the second half of the 13th century the musicians adopted a notational system that permitted them to deduce the note values by the shape and form of the ligatures. The remnant ambiguity of the pre-Franconian ligatures lasted until Franco of Cologne fixed a definitive and clear-cut system of ligatures. With Franco’s most prominent notational reform a unequivocal system to distinguish rhythmic combinations of short and long note values was fixed.

usical notation has always a practical function: composers, singers and musicians have to deal with it in a pragmatic and efficient way. Ambiguous notational signs were always a problem. Also the ligature system you discovered earlier was not ideal for the musical practice. As can be seen in the table of the previous step the pre-Franconian ligatures used in the earlier parts of the Codex Bamberg (Staatsbibliothek, Lit. 115) and Codex Montpellier (Faculté de Médecine H 196) still remain slightly flexible in their meaning, allowing different readings depending on their contexts.

Looking back, they can thus be considered some sort of transition towards the fixed ligature rules which were set by Franco of Cologne in his treatise Ars Cantus Mensurabilis (around 1280) and which, in their strictness and clarity, brought a new notational flexibility that ended the constraints of the modes.

Francos ligature rules took as their starting point the ‘standard’ square notation appearance of two- or three-note neumes (pes, clivis, torculus, porrectus, climacus, scandicus). He established, that a ligature has a beginning and an end (its first and last note). The beginning could be cum proprietate (with property) and sine proprietate (without property), the end of the ligature could be cum perfectione (with perfection) and sine perfectione (without perfection). If the ligature had the standard neume appearance, it was deemed cum proprietate and cum perfectione and the first and last notes were translated as brevis-longa. The standard appearance could be modified by either adding or removing stems, turning note heads or replacing square with oblique note forms.

Ligatures written according to the rules of Franco of Cologne. Signs become distinct.

L = longa; B = brevis; SB = semi-brevis

click to expand

Let us take the pes as an example. If the second note was turned right, the ligature lost its perfectio and had to be read brevis-brevis. If one added to this modified pes a stem on the right side of its first note, it also lost its proprietas and was thus read longa-brevis. If such a stem was added to the right side of the first note of an unmodified pes, the ligature lost its proprietas but kept its perfectio and hence signified longa-longa. An upward stem at the beginning of the ligature indicated opposita proprietas (opposite property) and, like in pre-Franconian ligatures, produced two semi-breves.

The clivis could undergo similar modifications. While in its standard form it meant brevis-longa (cum proprietate et cum perfectio), it lost its proprietas when the stem on the left side of the first note was removed and was then translated as longa-longa. If the stem was kept but the second note was transformed into an oblique form, it lost its perfectio (making brevis-brevis). If the stem was removed from this oblique ligature, it was regarded as sine proprietate et sine perfectio and thus read as longa-brevis. Again, the upward stem produced two semi-breves.

Ligatures with three or more notes functioned according to the same principles that are shown in the table above. Middle notes were always regarded as brevis unless a downward stem was drawn on the right side of any note within the ligature. The upward stem at the beginning of a note (opposita proprietate) was only applied to the first two notes in the ligature, turning them into semi-breves.

License

Copyright: University of Basel

Downloads