KNOWLEDGE PRODUCTION

4.4

Interdisciplinary co-production: collective intelligence and cognitive justice

Interdisciplinary work is a complex process that capitalises on the theoretical and methodological skills of several disciplines while involving them in a dynamic of dialogue and transformation. Each discipline can be conceived as an epistemic monoculture operating within a specific scientific community.

Entering an interdisciplinary co-production process requires thinking and putting into practice an intercultural dialogue that makes sense between and at the interface of disciplinary, scientific, and extra-scientific cultures. The philosophy and values of interdisciplinarity place the ethical principle of pluralism at the forefront, not only at the epistemological level, but also at the personal and organisational levels. It is about allowing, letting live, and making productive the diversity of groups and subgroups of culturally different but complementary people. It is an application of the systemic principle of diversity in unity and unity in diversity.

This free expression of the plurality of knowledge, identities, and practices represents a right to the existence and expression of different forms of knowledge and identities that can coexist, interact, and transform the disciplinary system in and through the process of interdisciplinary co-production. The (equitable and democratic) sustainability of knowledge depends on this recognition of diversity. This dialogical dimension is in a way a necessary condition for the development of disciplines and interdisciplinarity, while addressing the increasingly complex problems of our society (environment, global health, north-south relations, etc.).

To fully understand and apply this dialogic and intercultural logic of the interdisciplinary co-production process, the following two concepts of collective intelligence and cognitive justice are articulated.

a) Collective intelligence

Interdisciplinarity requires the implementation of a collective intelligence in the sense that each individual disciplinary specialist uses his cognitive, theoretical, and methodological abilities, while contributing and transforming himself into a collective and community dynamic that goes beyond him.

Each specialist has only a partial vision of the problem to be solved, and it is the collective intelligence of the group that allows to conceive and treat the problem in its entirety and to bring relevant and adapted solutions. This synergy between and beyond disciplinary monocultures allows the emergence of a global, negotiated, shared, and integrated vision, based on individual and collective skills.

Each specialist finds an interest in interdisciplinary collaboration, and this offers a new vision irreducible to only one of the mobilised disciplinary points of view.

b) Cognitive justice

In an interdependent and complementary way, the concept of cognitive justice defends the idea of a plurality of knowledge and questions the limits of purely disciplinary paradigms. It invites productive dialogue between academic and non-academic, local, and global knowledge for a sustainable, equitable and democratic world. It thus evokes and aims at an ideal of expression of different forms of knowledge and the right to the recognition of their specificities and their co-existence.

Cognitive justice also questions the hegemony of western science that creates asymmetries and injustices towards developing countries and non-western cultures. It is then a matter of recognising and including indigenous knowledge in an intercultural and interdisciplinary process without forcibly assimilating it to western scientific standards.

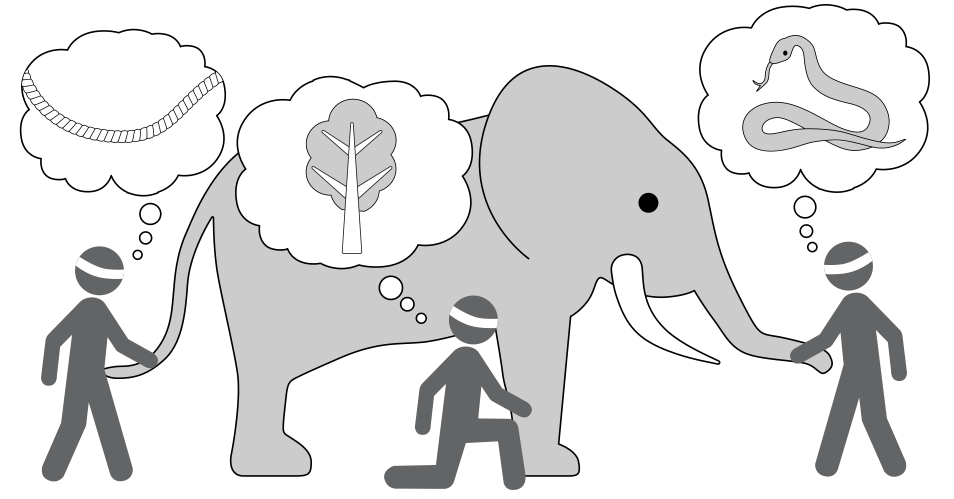

Fable of the blind men and the elephant

For illustration and personal and/or group reflection, consider the famous fable of the blind men and the elephant. Each of the six blind men touches a specific part of the elephant, perceiving a characteristic element from which he builds a mental representation.

The blind men and the elephant

For the man who touches its side, the elephant – from that man’s point of view – seems to be like a wall. Another man who explores its tusks describes it as a spear. The next touches its trunk and says it is like a snake, etc.

If everyone strongly and firmly defends his limited point of view, tugging at the object from all sides, and is potentially right, they are collectively wrong in their inability to articulate their perspectives for a comprehensive understanding of the elephant’s identity.

Think of the concepts of collective intelligence and cognitive justice in your experiences and projects. Are you sensitive to possible cognitive injustices? What could you undertake to reinforce a dynamic of interdisciplinary co-production? Note your thoughts and create a mind map. You may want to upload your findings on the whiteboard as well?

Author: Prof. Frédéric Darbellay

References

Darbellay, F. (2015): The gift of interdisciplinarity: towards an ability to think across disciplines. International Journal for Talent Development and Creativity (IJTDC), 3(2), 201-211.

Knorr-Cetina, K. (1999): Epistemic Cultures: How the Sciences Make Knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Visvanathan, S. (1997): A Carnival for Science: Essays on science, technology and development. London: Oxford University Press.

Downloads