ONE HEALTH QUALITATIVE AND MIXED METHODS

4.4

Illness vs disease of medical anthropology

Medical anthropology is a subfield of anthropology. It draws upon social, cultural, biological, and linguistic anthropology to better understand factors which influence health and well-being.

These factors include (see Geertz 1973):

-

the experience and distribution of illness

-

the prevention and treatment of sickness, healing processes

-

the social relations of therapy management and the cultural importance and utilisation of pluralistic medical systems

Arthur Kleinman shaped the concepts of illness and disease. While disease is regarded as a natural phenomenon (etic view), illness is conceptualised as a cultural construction (emic view) (Kleinman 1981).

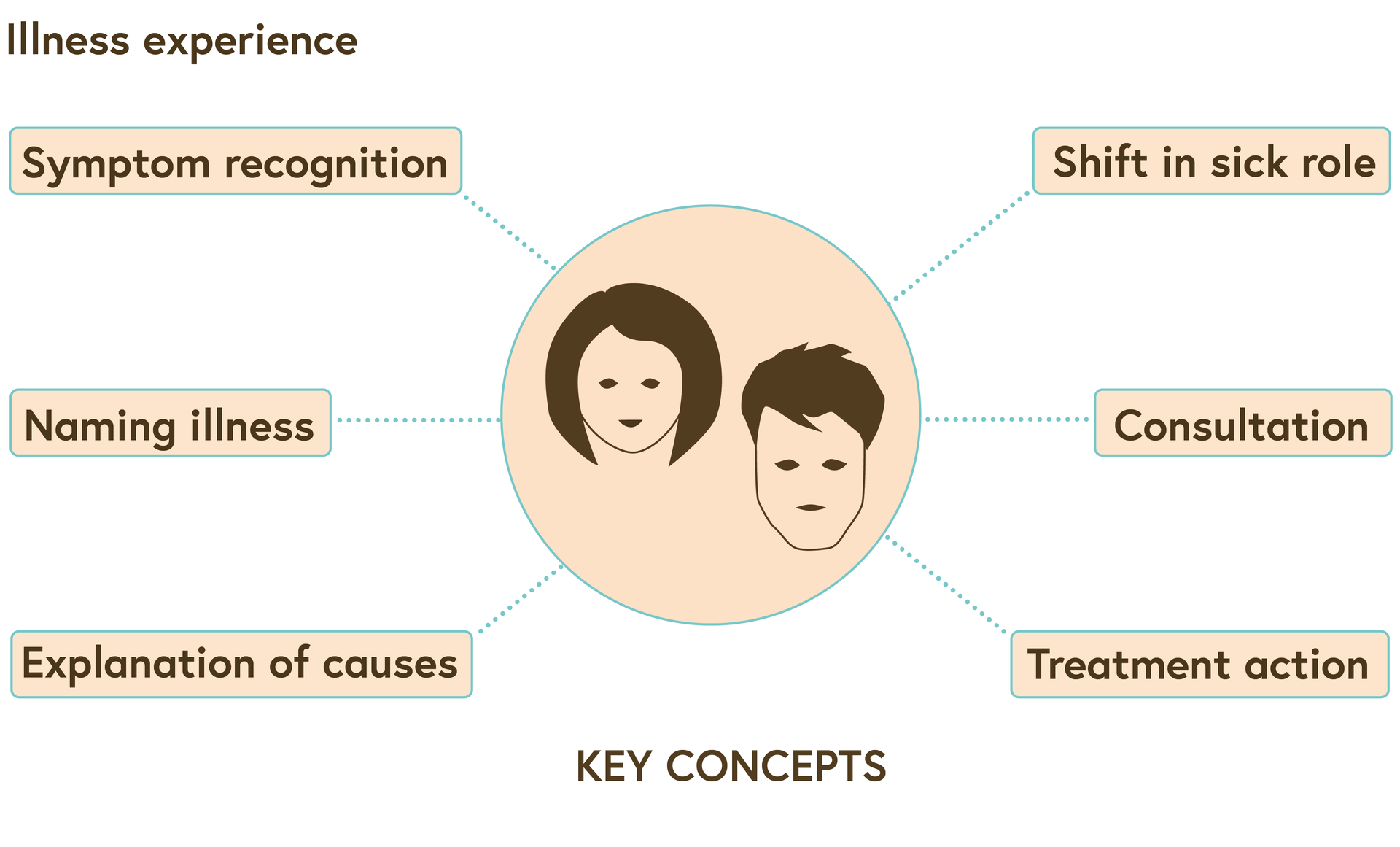

Key concept in illness experience

© Swiss TPH

The image above illustrates that illness representations focus around culturally embedded symptom recognition, naming illness and explanation of causes. These result in specific treatment-seeking behaviour and consultations. Illness representations are influenced by the context that includes, for example, rich vs poor strata of society, urban vs rural; educated in ‘modern’ schools vs illiterate people, and men vs women.

Once illness perceptions and their representations are clear, health-seeking behaviour of specific groups, such as the Fulbe in Chad, can be better understood. Fulbe pastoralists’ system of norms and values – pulaaku – includes the fulfilment of duties and expectations between Fulbe and encompasses a high degree of self-control to not express discomfort in public. This may result in seeking health services only at an advanced stage of disease, for example of brucellosis or tuberculosis.

However, there is a risk of misinterpreting or overestimating the impact of pulaaku since it is clearly one among several aspects influencing the Fulbe pastoralist health-seeking behaviour. Since the Fulbe perceive the treatment success in health facilities as being low, using health services is not of high priority for them.

Furthermore, perceiving an illness as life threatening, or not, also influences the health-seeking behaviour. If fuli/ sondarow (local concepts of tuberculosis) are experienced as ‘normal’ illnesses that come and go, there is no necessity to invest in expensive (bio-medical) treatment. Geographical distance can also have an impact on health-seeking behaviour, however, it was not seen as the most important barrier in Chad (Krönke 2004).

From the above example it becomes clear that one needs to know the local context that can provide new angles on how to mitigate a health problem. Medical anthropologists largely use qualitative methods. The goal of qualitative research is the development of concepts which help to understand social phenomena in natural, rather than experimental, settings, giving due emphasis to the meanings, experiences, and views of all participants. This is only possible if there is trust between interviewee and interviewer.

Observation is one of the most important methods used during qualitative data collection. Thus a fieldworker must be open in order to discover phenomena. Observations are used to learn about the following aspects:

- what people do (practices)

- (non-verbal) communication

- social interactions

- events and settings

Interviews are a very popular way of gathering information. They provide a way of generating empirical data asking people to talk about their lives and experiences. Interviews vary from structured to free-flow informational exchange. Informal conversational interviews occur naturally, eg when spontaneously meeting farmers with their cattle at a market, and are unstructured. Questions flow from the immediate context and situation. They allow for maximum flexibility in pursuing topics in whatever direction appears to be appropriate.

Focus Group Discussions are a way of collecting qualitative data by engaging a small number of people in a focused discussion. This could be, for example, a group of pastoralists sharing experiences related to animal health. The researcher acts as a moderator, posing questions, keeping the discussion flowing and allowing all participants to participate fully. It is usually recorded, transcribed and analysed following conventional analysis techniques (Silverman 2004).

Anthropologists acknowledge that data collection is always influenced by the background of the data collector and the respondents. Doing so, they recognise the power asymmetry involved in conducting qualitative studies. Crucial issues to think about are, for example, that the researcher’s personal life history and experiences, as well as race, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, and ideology can be influential. Having separate discussions with men and women is frequent. All of this needs to be taken into account when methods are designed, data is analysed and findings are presented. And, as is true for all studies collecting data and/or samples from study participants, the study protocols must undergo ethical approval including an informed consent form.

References

Geertz, C. (1973). Interpretation of Culture, New York, Basic Books.

Kleinman, A. (1981). Patients and Healers in the Context of Culture. An Exploration of the Borderland between Anthropology, Medicine, and Psychiatry, Berkeley, University of California Press.

The following article is in German with an English summary: Krönke, F. (2004). Hilfesuchverhalten und die Barrieren der Nutzung des öffentlichen Gesundheitswesens bei pastoralnomadischen FulBe im Tschad, in: Anthropos 99, 25-38.

Silverman, D. (ed.) (2004). Qualitative Research. Theory, Method and Practice (2nd ed.), London, Sage Publications.

License

University of Basel