SURFACE READING & THE MATERIALITY OF COMMUNICATION

6.10

What is remediation?

When Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin published ‘Remediation: Understanding New Media’ in 1999, it was immediately clear that their title referred to Marshall McLuhan’s earlier ‘Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man’ (1964).

Bolter and Grusin sought to update McLuhan’s findings − particularly his contention that ‘the “content” of any medium is always another medium’ (McLuhan 8) − for the digital age.

Cover of Bolter and Grusin’s Remediation (© The MIT Press)

For Bolter and Grusin, media history is not a series of displacements in which new media (e.g. the internet) make old media (e.g. the radio) obsolete. Instead, new media transform older media, retaining some of their features while discarding others. In their own words, remediation is ‘the way in which one medium is seen by our culture as reforming or improving upon another’ (59); it is ‘the formal logic by which new media refashion prior media forms’ (273).

Think of how the laptop adopts features of earlier media such as the typewriter and the television and transforms them into something different.

Yet remediation can also work the other way around. Challenged by the appearance of new, more efficient media, older media also adopt features of more recent media to survive in a changed media environment. Think of how, challenged in cultural significance and sale numbers by the new medium of computer games, the old medium of (Hollywood) movies increasingly incorporates CGI (computer-generated imagery) and narrative structures that resemble those of computer games. Bolter and Grusin call this ‘retrograde remediation’:

Animated films remediate computer graphics by suggesting that the traditional film can survive and prosper through the incorporation of digital visual technology. Full-length animated films, especially the Disney films of the past decade [1990s], are perfect examples of ‘retrograde’ remediation, in which a newer medium is imitated and even absorbed by an older one. (147)

A good number of the books published by the McSweeney’s publishing house are examples of retrograde remediation that not only adopt hypertextual structures familiar to computer users but also have a haptic, sensual quality that sets them apart from most texts read on computer screens. Consider, for instance, McSweeney’s Issue 16, which sports two slim books, a set of playing cards that tell a story written by Robert Coover and which changes whenever the cards are shuffled, and a comb.

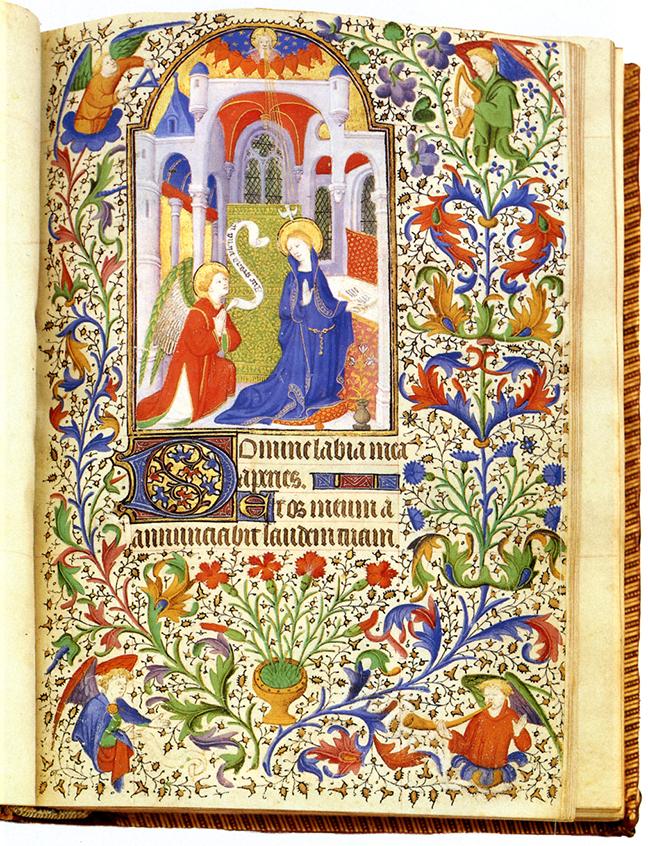

Book of hours, Paris ca. 1410 (© Wikimedia, public domain)

Bolter and Grusin outline two major strategies in the medial competition between old and new media. McSweeney’s Issue 16 exemplifies ‘hypermediacy’, a ‘style of visual representation whose goal is to remind the viewer of the medium’ (272).

An earlier example of hypermediacy would be medieval books of hours, which contain beautiful illustrations that draw readers’ attention to the materiality of the book itself.

The other remediation strategy is ‘transparent immediacy’, where the goal is the opposite of hypermediacy: to make the reader or viewer forget the medium and give in to the illusion that what they experience is immediate and direct. Examples of transparent immediacy are 3D movies and fantasy novels that invite us to suspend our disbelief and immerse ourselves in a fictional world, making us forget about the outside world and the fact that we are holding a book in our hands. In Bolter and Grusin’s words, transparent immediacy is a ‘style of visual representation whose goal is to make the viewer forget the presence of the medium (canvas, photographic film, cinema, and so on) and believe that he is in the presence of the objects of representation’ (272–73).

References

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: MIT Press, 1994.

License

University of Basel