TRANSDISCIPLINARITY – INTRODUCTION AND CLARIFICATION

2.7

Sichere Migration – Kontext der Herkunfts- und Aufnahmeländer

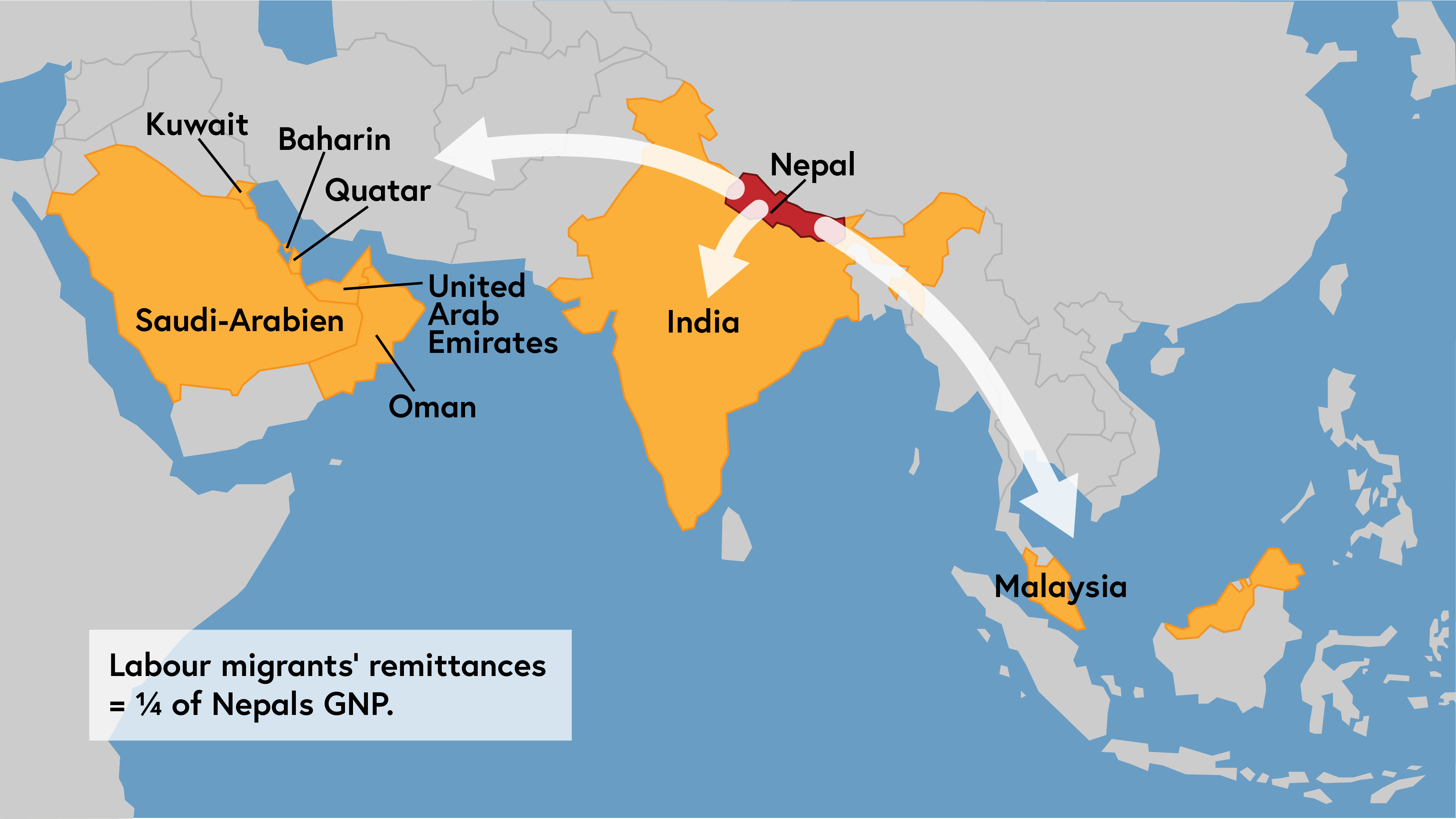

Es gibt verschiedene Gründe, warum internationale Arbeitsmigration in Nepal zunehmend zu einer wichtigen Einkommensquelle geworden ist. Im Jahr 2013 betrug die offizielle Gesamtsumme der Überweisungen 25 % des nepalesischen Bruttonationalprodukts – ohne die nicht erfassten Beträge.

Nepalesische Migration

Armut, Arbeitslosigkeit, schwindende natürliche Ressourcen und politische Instabilität sind die Hauptgründe dafür, dass internationale Arbeitsmigration zunehmend zu einer wichtigen Einkommensquelle geworden ist. Neben politischer und wirtschaftlicher Instabilität ist die Migration auch ein „Übergangsritus“, insbesondere für junge Männer, der ebenso zentral für ihren Übergang ins Erwachsenenalter ist wie eine Türöffner für formale und informelle Bildung und die Aneignung von Erfahrungen, die für weitere Mobilität zentral sind.

Die internationale Migration aus Nepal hat in den letzten Jahrzehnten stetig zugenommen. Offiziell sind mittlerweile 6,8 % der über 29 Millionen Einwohner abwesend, davon 12 % Frauen.

Während Indien lange Zeit das wichtigste Ziel war, haben sich die Migrationsziele diversifiziert. Im Zeitraum 2011/17 arbeiteten und lebten noch 41 % aller nepalesischen Migranten in Indien, aber die Golfstaaten beherbergen mittlerweile 38 % aller nepalesischen Migranten, 12 % in Malaysia und weitere 9 % in anderen Ländern.

Zu diesen „anderen“ Ländern gehören nepalesische Krankenschwestern, die im Vereinigten Königreich, in den USA, Neuseeland und Australien arbeiten, sowie eine wachsende, aber noch wenig erforschte Gruppe von Studenten (62.391 nepalesische Studenten studierten 2011 im Ausland) – von denen viele ebenfalls Überweisungen nach Hause schicken.

Nepalesische Armut

Die Nepal Living Standard Survey bestätigte deutliche Fortschritte bei der Erreichung des ersten Nachhaltigkeitsziels, SDG 1 (Beseitigung extremer Armut), wobei die Armutsrate von 31 % in 2003/4 und 42 % in 1995/96 auf 23,5 % für 2010/11 sank.

Es gibt jedoch erhebliche regionale Unterschiede bei der Armut, wobei die Hochgebirge und die westlichen Hügelländer einen höheren Armutsanteil und einen langsameren Rückgang aufweisen als das Terai (Tiefland) und die östlichen Teile des Landes. Obwohl Migration und Überweisungen sicherlich nicht der einzige Faktor für den Rückgang der Armut sind, liefert ein genauer Blick auf die Migrationsziele einige mögliche Korrelationen.

Die Rolle von Überweisungen

Im Jahr 2013 betrug die offizielle Gesamtsumme der Überweisungen 5 Milliarden US-Dollar oder 25 % des Bruttonationalprodukts, wobei geschätzt wird, dass 35 % der Überweisungen nicht erfasst werden (siehe hier).

Auf Haushaltsebene bedeutet dies, dass 56 % der Familien in Nepal Überweisungen erhalten, die 31 % ihres Haushaltseinkommens ausmachen. Obwohl 41 % der Bevölkerung in Indien arbeiten, stammen nur 11 % der Überweisungen aus Indien, während 26 % aus den Golfstaaten (insbesondere Saudi-Arabien und Katar), 8 % aus Malaysia, 35 % aus anderen Ländern und 20 % aus interner Migration stammen.

Verschiedene Studien deuten darauf hin, dass die nach Indien gehenden Arbeitsmigranten hauptsächlich aus den Bergen und Hügelländern, insbesondere aus dem Westen Nepals, stammen. Obwohl Überweisungen insgesamt zur Armutsbekämpfung beitragen, gibt es Hinweise darauf, dass die Begünstigten von Überweisungen eher in städtischen Gebieten in den zentralen und östlichen Regionen Nepals ansässig sind, mit Mitgliedern, die in anderen Ländern als Indien als Migranten tätig sind. Ebenso profitieren wohlhabendere Familien am meisten von Überweisungen.

Obwohl weit weniger Überweisungen aus Indien stammen als aus anderen Ländern, bleibt die über Generationen etablierte Mobilität zwischen Nepal und Indien für viele, insbesondere in der westlichen Region des Landes, von Bedeutung. In ländlichen Haushalten mit geringem Bargeldeinkommen können selbst kleine Geldtransfers sehr wertvoll sein, um die Risiken von Saisonalität, Ernteausfällen und Nahrungsmittelknappheit zu reduzieren.

Es müssen auch andere als finanzielle Aspekte berücksichtigt werden, wie beispielsweise das Senden von Gütern. Die Anwesenheit von Familienmitgliedern in Indien erleichtert den Zugang zu medizinischer Versorgung und Schulbildung in Indien, und Migranten decken diese Kosten, anstatt Geld nach Nepal zu schicken.

Jobanzeigen (Foto: Alice Kern)

Abreisende Migranten am Flughafen Kathmandu (Foto: Ulrike Müller-Böker)

Migrationsmuster zwischen Nepal und Indien

Obwohl sich die Migrationsmuster zunehmend diversifizieren, bleibt das Nachbarland Indien das wichtigste Ziel. Dies gilt auch für die vorliegende Fallstudie über Menschen aus der Fernwestlichen Entwicklungsregion Nepals.

Migration wird seit Generationen praktiziert und es haben sich grenzüberschreitende Netzwerke aus Verwandten und Freunden entwickelt. Die Mehrheit der Migranten sind Männer. Frauen reisen für kürzere Zeit nach Delhi, insbesondere zur medizinischen Behandlung und Geburt.

Die Migranten verfügen in der Regel über begrenzte Bildung und finanzielle Mittel. Daher sind sie auf grenzüberschreitende Familien- und Verwandtennetzwerke angewiesen, um sich in Delhi zu etablieren. Der Arbeitsmarkt ist beispielsweise hoch organisiert, da Jobs innerhalb von Netzwerken verkauft werden. Für finanzielle Bedürfnisse gründen Migranten eigene informelle Spar- und Kreditvereinigungen.

Oft erlernen sie jedoch keine neuen Fähigkeiten, verschulden sich aufgrund schlecht geführter Selbsthilfegruppen und Glücksspiels noch mehr und haben mit schlechten Arbeits- und Lebensbedingungen zu kämpfen. Ihre geringe Bildung, informelle Arbeit und fehlenden weitreichenden sozialen Netzwerke tragen dazu bei.

Obwohl die Migranten die Migration hauptsächlich als Chance sehen, tun sie dies mit erheblichen sozialen Kosten und es kann zu Verschuldung und Abhängigkeit führen und dazu führen, dass sie ihr ganzes Leben lang Migranten bleiben.

Insgesamt muss internationale Migration auch als ein hochselektiver und ungleicher Prozess in Nepal betrachtet werden, der tief in sozialen Netzwerken durch Freunde, Familie oder Vermittler oder die Verfügbarkeit von Informationen und Startkapital verwurzelt ist. Menschen mit mehr Startkapital und größerem Zugang zu Informationen gehen eher zu Zielen mit höheren Verdiensten, was oft zu höheren Überweisungen führt.

Thieme, S. (2017): Educational consultants in Nepal: Professionalization of services for students who want to study abroad. In: W. Lin, J. Lindquist, X. Biao & B. Yeoh (Eds.), Special Issue ‘Migration infrastructures and the production of mobilities’, Mobilities 12(2), 243-258.