PATTERNS THAT HELP

3.4

Plotlines and “Moves”

How we tell our stories is often linked to subliminal and deep-rooted cultural patterns. No achievement without hindrance, what rises must fall and vice-versa: we refer to visions of fate to make tales interesting. Plots evolve according to certain structures – as do factual reports.

Think of a video abstract as a sort of audio-visual argumentation. As we have seen, you need to present your research in a succinct and understandable way. Think about how to organise your points in a convincing sequence that keeps the interest of your audience.

Throughout our lives we are confronted with stories in many guises. The way they are organised belongs to a cultural repertoire with which we are familiar even if we have not analysed it. If you have watched blockbuster monster films, you will for instance be aware that the danger has never passed the first time the monster is killed: it will come back and make its last stand – a moment you expect, but do not know when exactly it will happen, so the film keeps you anxious and on the edge of your seat. This is what plotlines and dramaturgy do: they play with your expectations, put you on high alert, surprise you and tie you to the narrative.

The way we structure a plot is highly dependent on our culture. Thus, there is not one way to do it right. In addition, you will find these plotlines not only in fiction, but also in reports about facts and figures.

How does Western dramaturgy divide a plot into acts? As an example, we will take the European classical division of a drama into five acts. Plotlines depict the development of the principal character.

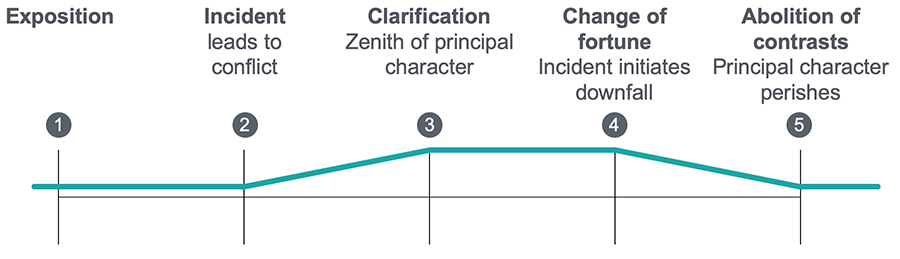

Plotline classical tragedy

In a classical tragedy, we are first introduced to the dreams and drives of the protagonist. This part is also called exposition. At the beginning of Act II, an incident leads to a conflict that challenges these dreams and with them our hero or heroine. He or she then addresses the conflict. This gives rise to hope, and in Act III the conflict seems solved in favour of the main character, with his or her situation much improved. Towards the end of this act, however, another incident initiates the downfall of the hero or heroine that covers Act IV. In Act V, the conflicts are solved in a way that is detrimental to the protagonist, a classical tragedy typically ending with his or her death.

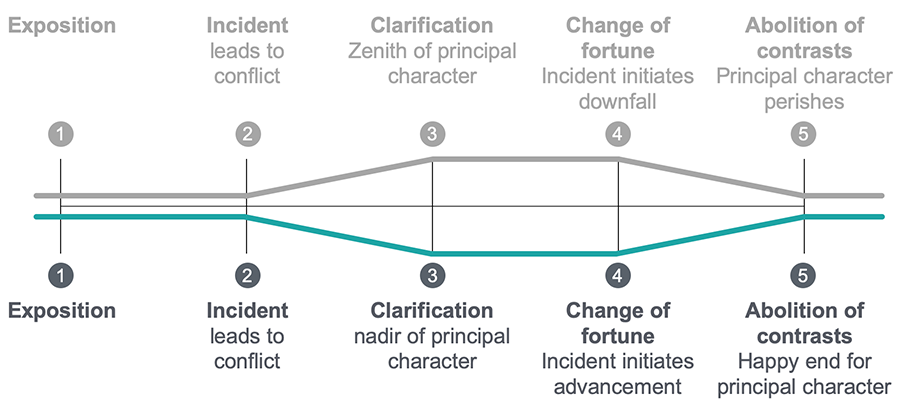

Plotline classical comedy

A classical comedy follows a mirrored plotline, with zenith and nadir of the main character exchanged.

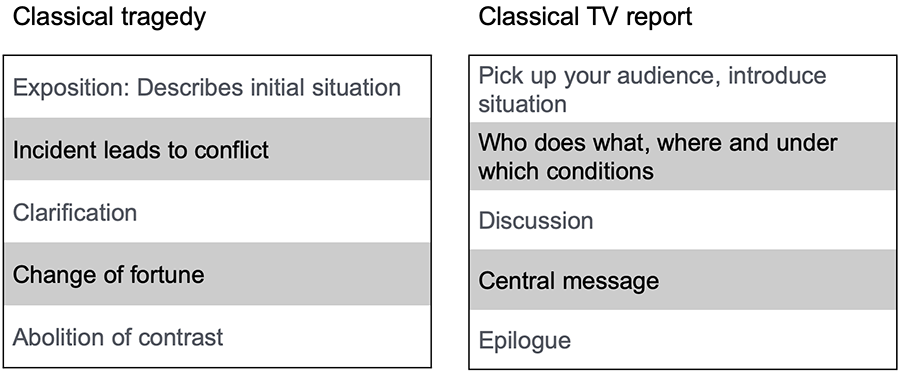

As mentioned, these plotlines have many variants and also depend heavily on genre. But consider the following schema that – many years ago – was used in the training of television journalists. It clearly links the five acts to the structure of a TV report.

Dramaturgy and argumentation

The exposition is used to involve the audience, to introduce the topic and situation. The second part conveys basic information – usually the who, the what, the where and the when. This is how the report sets up the topical aspects of a situation, making it newsworthy at exactly the point where in tragedy we see an incident leading up to a conflict. The report follows this with a discussion of the facts; in classical drama, this corresponds to the act that initiates clarification. The change of fortune in classical drama compares to the moment in the report when the audience would expect to hear the main statement: what is the conclusion, what should the audience remember? Finally, the epilogue is the part in which the report wraps up – it gives the audience food for further thought or perhaps an outlook.

Obviously, this analogy refers to a certain age of television reports that were built on the assumption that the audience followed a sequence of broadcasted events without many possibilities to interact. Today, we see different genres on the web as well as on TV. Mostly, they celebrate interaction – be it by stand-ins (live reports, discussions), be it by addressing the public much more directly.

Linguistics provides a further instrument to analyse the sequence of rhetorical functions in a given genre. It may analyse the so-called moves in a text, a move being a unit of varying size (a clause, one or more paragraphs) with a specific function. Jianxin Liu (2019) published an article in the Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, in which he subjects video abstracts to move analysis. He starts from move analysis examining research article abstracts, adapting them to the analysis of video abstracts. In respect to written abstracts, we again encounter five moves:

[…] Hyland’s (2004) pro five-move model comprising (a) introduction, (b) purpose, (c) method, (d) product, and (e) conclusion (Lu, 2019, p. 6)

Unfortunately, this article is not freely available. But analysing moves in video abstracts seems a promising way to understand a genre that is still evolving.

When you produce your video abstract, you should be aware that you are dealing with an audience that is unconsciously or consciously familiar with certain patterns. If you want to be understood quickly, you should use these patterns. And another take-away: if you are used to scientific texts, you might first argue your main point, then follow it up by a discussion and lead up to the conclusion. However, in video abstracts, that might not be the best approach – you need to first familiarize your audience with the context, getting their attention, before you wow them with your main statement.

References

Liu, Jianxin (2019). Research Video Abstracts in the Making: A Revised Move Analysis. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication

Hyland, K. (2001). Disciplinary Discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

License

University of Basel