DIVING INTO THE CASE: THE ENERGY SYSTEM AND TRANSITION

3.3

Energy: The demand side

Whether we use our computer, heat our apartment, take the car, or purchase groceries: we need energy. The resulting demand for energy is driven by our need for so-called energy services, taking into account that we do not consume energy directly but need it in order to fulfil our needs in everyday life.

There have been many attempts to categorise consumer consumption behaviour or, in other words, our demand for energy services into overarching categories. A broad classification distinguishes between action-specific, i.e. direct consumption and material-specific, i.e. indirect or embodied consumption (Burger et al., 2015).

The latter takes into account that even when our actions do not directly result in energy consumption, they may indirectly be associated with energy demand, for instance when we buy products that require energy during the production and transportation processes. In a nutshell, consumption can include several dimensions that should be taken into account if we want to aim for a more sustainable behaviour change.

In the context of the energy transition, the term “energy demand” seems to be closely linked to the word “change”, as energy demand inevitably needs to be reduced in order to advance sustainable energy transitions. So, what can we do to change our demand for energy in a sustainable way?

In line with what we learnt about sustainability strategies before, we can “reduce” and “improve” energy consumption actions corresponding to a sufficiency and efficiency strategy, respectively. Coming back to our two categories of “action-specific” and “material-specific” consumption, this means that we can, for instance, reduce room and water temperature or improve efficiency of products by purchasing more efficient products.

Recent systematic analyses have shown that these energy consumption changes hold great potential for reducing energy demand and associated emissions, while ensuring high levels of well-being (Creutzig et al., 2022). Knowing what needs to be changed, however, does not necessarily mean that we know how to change behaviour. To this end, we need to better understand the determinants of energy consumption behaviour.

Various scientific disciplines including psychology, economics, and sociology strive to answer these questions:

- What factors and mechanisms determine our energy consumption behaviour?

- How can sustainable behaviour change be promoted?

Research in psychology, for instance, illustrates that energy demand behaviour is driven by individuals’ belief structures, values, emotions, and their perception of social norms about the action at hand.

Research in economics illustrates the importance of price structures and demographic factors such as household income for energy consumption behaviour.

In contrast, sociology emphasises the relevance of symbolic meanings of energy actions and practices.

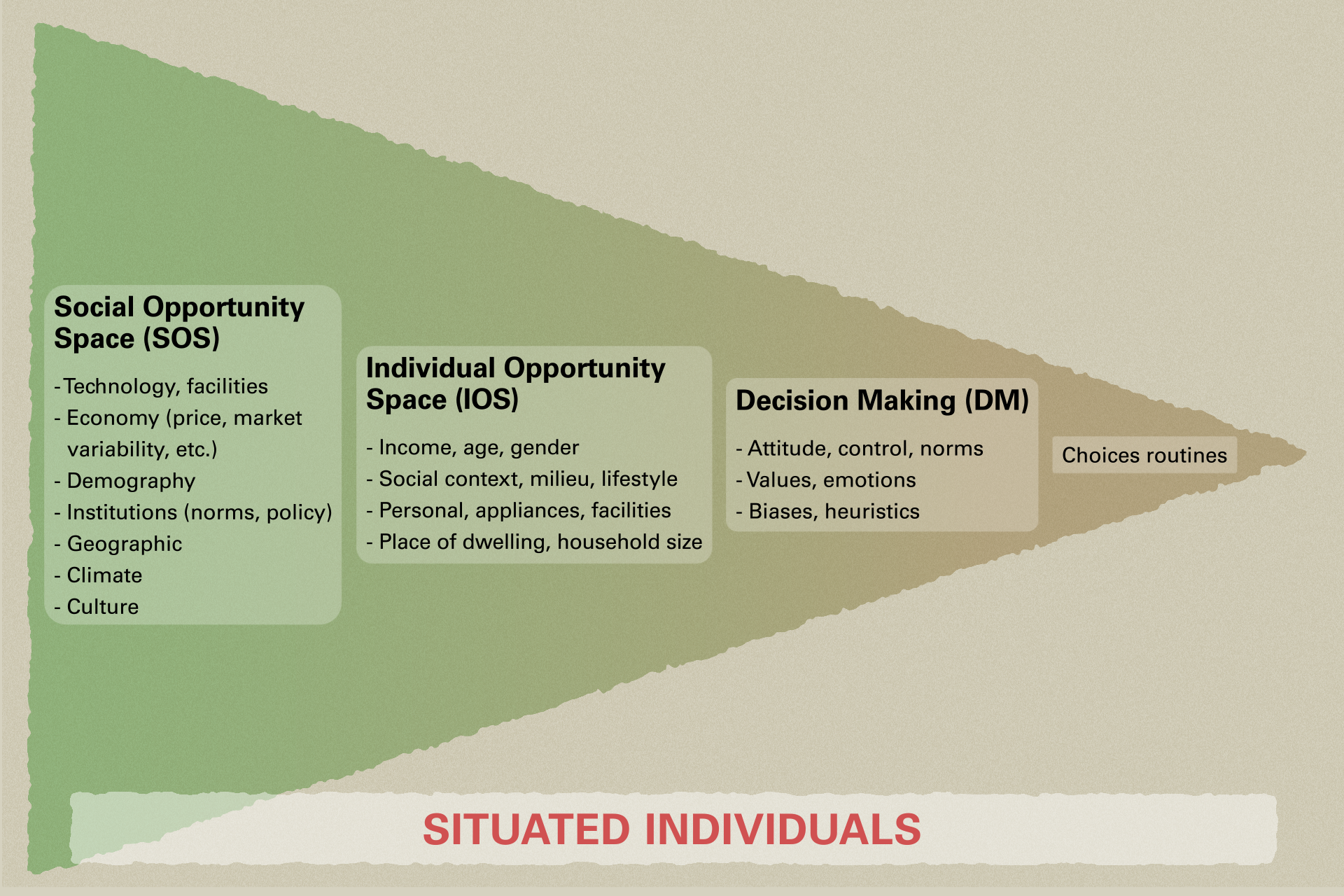

In the last decades, these disciplines mostly worked within their disciplinary silos. Interdisciplinary models that integrated the different insights are still lacking. One exception is the research by Burger and colleagues (2015), who integrated insights about determinants of energy consumption behaviour from different scientific disciplines into one joint framework, which incorporates the following determinants of energy consumption behaviour and change:

- The social opportunity space encompasses macro-level aspects such as economy, technological advancement and availability and culture – aspects that cannot be changed by the individual

- The individual opportunity space encompasses micro-level aspects such as personal income, personal appliances, and social context – aspects that can be, partially, changed by the individual

- Individual decision-making encompasses determinants such as belief structures, values, and emotions and individual decision-making processes

According to this framework (cf. Figure 1), individuals are situated within opportunity spaces that may hinder or facilitate sustainable behaviour change. As a consequence, individual energy-related decisions are not made in isolation, but rather depend on an interplay between the contextual boundary conditions (i.e. opportunity spaces) and the specific characteristics of the individual.

Figure 1: Integrative framework of energy consumption behaviour from Burger et al. (2015), including opportunity spaces and individual decision-making. Figure adapted by the New Media Centre from Advances in Understanding Energy Consumption Behavior and the Governance of Its Change – Outline of an Integrated Framework. (see References below) (CC BY 4.0).

Figure 1: Integrative framework of energy consumption behaviour from Burger et al. (2015), including opportunity spaces and individual decision-making. Figure adapted by the New Media Centre from Advances in Understanding Energy Consumption Behavior and the Governance of Its Change – Outline of an Integrated Framework. (see References below) (CC BY 4.0).

If we know what determines behaviour and behaviour change, it is easier to develop interventions that promote more sustainable practices. According to the framework presented above, various levels – from social opportunity spaces to individual decision-making processes – can serve as “access points” for policy interventions.

On the level of social opportunity spaces, public policy could, for instance, aim to increase the availability of energy-efficient technology by providing targeted industry subsidies.

On the level of individual decision-making, public policy could, for example, introduce or improve energy efficiency labels for household appliances to make sustainable decision-making easier for consumers.

Whereas the content of public policies is important, we also have to consider the political and societal context in which the policies are implemented. Governance recognises that, in addition to pure policy content, political structures and processes should be taken into account when managing energy demand solutions. Ideally, this will lead to more sustainable energy consumption behaviour.

Author: Ulf Hahnel

References

Burger, P., Bezençon, V., Bornemann, B., Brosch, T., Carabias-Hütter, V., Farsi, M., Hille, S. L., Moser, C., Ramseier, C., Samuel, R., Sander, D., Schmidt, S., Sohre, A., & Volland, B. (2015). Advances in Understanding Energy Consumption Behavior and the Governance of Its Change – Outline of an Integrated Framework. Frontiers in Energy Research, 3.

Creutzig, F., Niamir, L., Bai, X. et al. (2021). Demand-side solutions to climate change mitigation consistent with high levels of well-being. Nature Climate Change 12, 36–46.