PRE-PSYCHOLOGY

2.4

Psychology as a Social Science

How did social physics and statistics inform psychology?

“Man is born, grows up, and dies, according to certain laws which have never been properly investigated, either as a whole or in the mode of their mutual reactions”. Thus stated Adolphe Quetelet in “Sur l’homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale”, published in 1835. Quetelet’s interest in statistical “laws” originated in mathematics and its applications to astronomy, but it was its application to social phenomena that revolutionized the social sciences and inspired others to use these ideas and methods when building a new discipline of psychology.

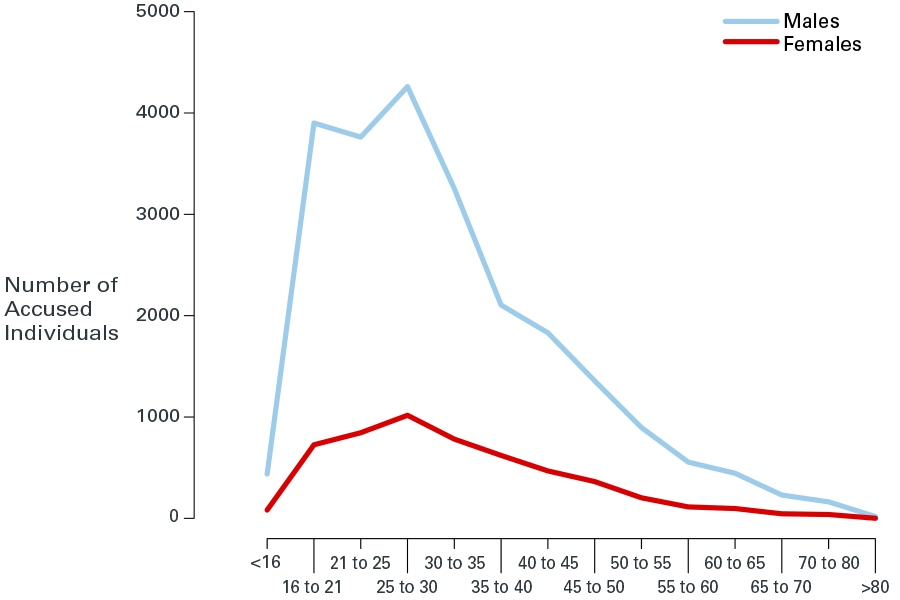

Adolph Quetelet was among the first to apply statistics to social science, planning to create a new area of research that he called “social physics”. His goal was to understand the statistical laws underlying “physical, moral, and intellectual qualities” by using evidence – census and administrative data – to uncover regularities, such as patterns of age and sex differences in crime, marriage, suicide, or artistic production.

Quetelet did not think these “laws” were fixed but, rather, believed in the possibility of intervention to promote social change. For example, in his analysis of the age-crime relation he wrote that although statistical tables seemed stable over time and “offered pretty nearly the same results” across several years they “may yet become gradually modified; it is to effect this modification that the friends of humanity ought to turn their attention.” Quetelet was interested in description and observation but, as this quote attests, in social betterment as well.

Quetelet’s work influenced many different areas of science, including economics and psychology, because it represented a prime example of the use of quantification and statistics to understand human and social phenomena (Jahoda, 2015).

Willhelm Wundt, for example, made reference to Quetelet‘s work in his lectures and writings in the 1860s and seemed inspired by such ideas when he wrote in 1862: “one can learn more psychology with statistical investigations than with all the philosophers, except for Aristotle”. One can tell that quantification through measurement and the use of data was deeply appealing to Wundt. Quetelet’s approach may have also helped convince Wundt of the need to broaden the scope of the new discipline of psychology which was initially largely focused on the functioning of single individuals in well-controlled laboratory settings.

As Kurt Danziger (1990), a historian of psychology, writes:

“For all his interest in experimentation Wundt was sufficiently immersed in the German tradition of objectifying Geist to reject the notion that a study of the isolated individual mind could exhaust the subject matter of psychology. (…) These investigations occupied Wundt increasingly in his later years and resulted in the series of volumes that he published under the general title Volkerpsychologie from 1900 onward. He now expressed himself to the effect that this was the more important part of psychology, which was destined to eclipse experimental psychology.”

Quetelet’s focus on social phenomena like crime, marriage, or suicide raised intriguing issues related to morality, free will, and the human passions that far extended the individualized mechanistic account of the mind. These topics continue to be major and fascinating facets of psychology today.

Propensity to Crime (France 1826−29): An age-crime curve based on one of Quetelet’s statistical table from 1830s that identified age and sex differences in criminality.

References

Danziger, K. (1990). Constructing the subject: Historical origins of psychological research. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511524059

Jahoda, G. (2015). Quetelet and the emergence of the behavioral sciences. SpringerPlus, 4(1), 473. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-1261-7

Please note that certain links to journal articles are only available within the eduroam network if they concern publications for which the university has a campus license. If you are a member of the University of Basel and want to access university resources from home, you will need to install a VPN client.

Lizenz

University of Basel