GESTALT PSYCHOLOGY

6.4

Lewin’s Equation and Brunswik’s Lens

Discover the legacy of Gestalt psychology behind some of Kurt Lewin’s and Egon Brunswik’s ideas.

Gestalt psychology put an emphasis on considering the relation between elements and describing the resulting emerging patterns. These ideas would influence further theorizing in psychology, leading to the development of new theories and areas of research. Read about two examples below.

Kurt Lewin’s Equation

Kurt Lewin is known as one of the pioneers of social and organizational psychology. Early in his career, Lewin had close contact with psychologists of the Gestalt school of psychology, including Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler. In his preface of “Principles of Topological Psychology” of 1936, Lewin addressed Wolfgang Köhler directly and suggested that psychology could profit from developing “a system of concepts which shows all the characteristics of a Gestalt, in which any part depends upon every other part”.

In his book, Lewin would go on to introduce field theory, which stated that a person’s life is made up of multiple distinct spaces that the person has to travail in order to achieve his or her goals. Crucially, echoing Gestalt principles, Lewin proposed that human behavior would have to be understood as the result of the combination of these different elements in a constructive process. Lewin would end up summarizing this idea in a simple equation which links behavior, B, to both the person, P, and the environment, E.

B = ƒ(P, E)

Although Lewin’s equation may appear trivial today, it was important in encouraging psychologists to consider how behavior is embedded in multiple physical and social contexts, which are central tenets in the theories of social and organizational psychology today.

Brunswik’s Lens

Egon Brunswik is best known for his work on perception. As a perception researcher, Brunswik was very familiar with the Gestalt principles being formulated by Wertheimer and colleagues, which gets ample reference in his early work (cf. Brunswik, 1937).

Brunswik took these ideas further, however, by emphasizing the functional nature of Gestalt principles. Why would the cognitive system follow the principle of continuity, for example? According to Brunswik, the perceptual system follows such a law because it is useful and allows the system to make good predictions in its environment. As a consequence, Brunswik sees the goal of psychology as understanding the adaptive link between the organism and its environment based on probabilistic principles:

”The primary subject-matter of psychology is defined by a formal criterion as the objective pattern of couplings which an organism, in its causal intercourse with the environment, was able to focalize in a fairly “constant” way upon more or less remote (life-sustaining) types of “objects,” despite the disturbing variability (multiplicity and ambiguity) of the single mediating stimulus-cues and means.”

According to Brunswik, the environment with which the organism comes into contact is an uncertain, probabilistic one. Adaptation to a probabilistic world requires that the organism learns to employ probabilistic, uncertain evidence – so-called proximal cues – about the world in the form of general laws or principles, such as those studied by Gestalt psychology.

Brunswik’s ideas about probabilistic judgement based on cues would go well beyond the psychology of perception and contribute to theories of judgment and decision-making that also understand human judgment as the integration of cues supplied by the environment (Hammond, 1955).

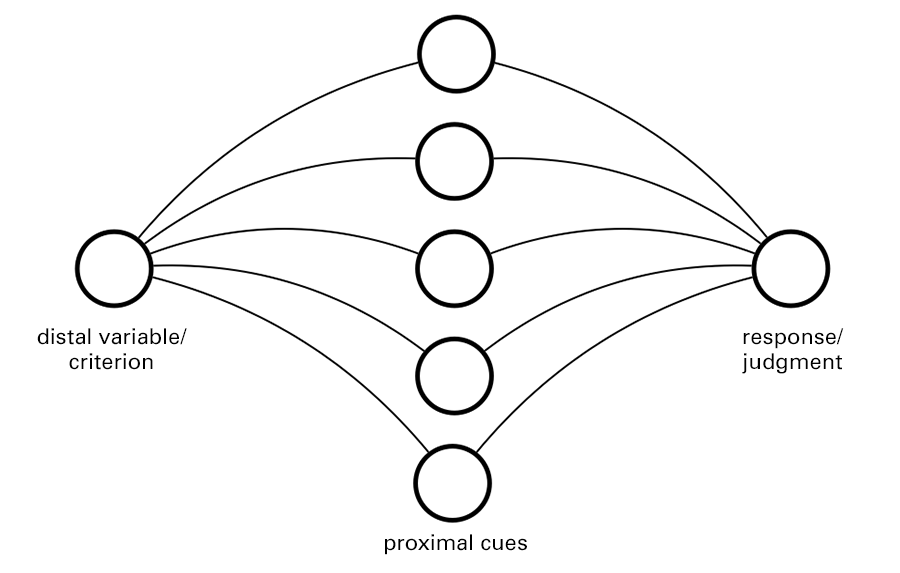

Why does the perceptual system follow the Gestalt laws? Brunswik’s system proposes that such laws are adaptive in the sense of allowing the system to make accurate inferences about the world. Brunswik’s focus on inference led him to propose that the system acts like a lens (Brunswik, 1943). In this analogy, a distal stimulus is perceived in terms of multiple proximal cues that are imperfectly correlated with each other and are integrated to “see” the correct percept. This idea has been extended beyond vision to understand all forms of judgment based on cues (Hammond, 1955).

(Author’s own work)

References

Lewin, K. (1936). Principles of topological psychology. McGraw-Hill. https://archive.org/details/PrinciplesOfTopologicalPsychology/page/n5/mode/2up

Brunswik, E. (1937). Psychology as a science of objective relations. Philosophy of Science, 4(2), 227-260. https://www.jstor.org/stable/184864

Brunswik, E. (1943). Organismic achievement and environmental probability. Psychological Review, 50(3), 272. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0060889

Hammond, K. R. (1955). Probabilistic functioning and the clinical method. Psychological Review, 62(4), 255–262.

Please note that certain links to journal articles are only available within the eduroam network if they concern publications for which the university has a campus license. If you are a member of the University of Basel and want to access university resources from home, you will need to install a VPN client.

Lizenz

University of Basel