PRE-PSYCHOLOGY

2.3

Psychology and the Natural Sciences

Biology, Neuroscience, Physiology

Psychology left the realm of pseudoscience by learning to link mind and brain through lesion studies.

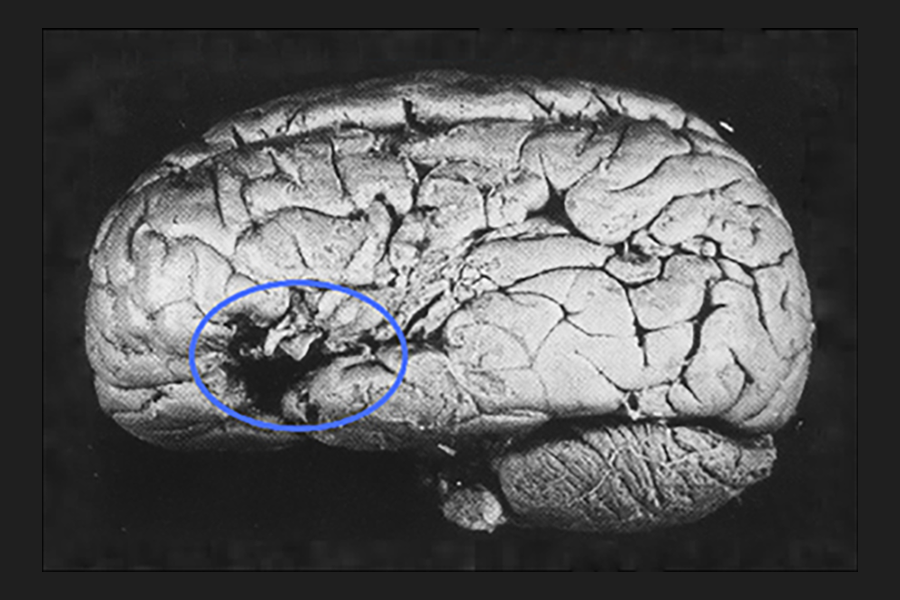

Paul Broca (1824-1880) is famous for, in 1861, having reported to the members of the Anthropological Society of Paris the case of Monsieur “Tan” – a patient who could only utter the word “tan” due to a brain lesion. This and additional observations of similar patients led Broca to propose in 1865 that a frontal portion of the left hemisphere was the part of the brain responsible for articulate speech – and which now receives the title of Broca’s area.

By presenting his work to his peers, Broca was engaging in a debate about the localization of psychological functions - in particular, language. The issue of brain localization had been getting attention in academic circles, largely due to earlier claims of phrenologists, like Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828), that they could tell and predict the personality and other psychological characteristics of individuals from the bumps on their heads. Phrenology was a pseudoscience that emerged from Gall and other phrenologists’ intuitions concerning the correlation between people’s personalities and the shapes and protuberances of their skulls. Now, Broca’s anatomical-clinical correlative method presented a new, more systematic way of understanding the link between brain and psychological functions.

Was Broca a maverick who single-handedly changed the scientific methods of the day? Hardly.

Broca’s contribution is more likely a good example of the zeitgeist that prevailed in the field at that time. The association between speech disorders and frontal lobe lesions had been already advanced by Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud in 1825. In turn, the hypothesis of left hemisphere dominance for language was first proposed by Marc Dax in 1836, also based on the observation of brain lesion patients. Broca’s methods and claims had been anticipated by over 30 years!

Two conclusions can be drawn from Broca’s example. First, this episode reminds us that historical accounts often forget the contribution of separate individuals and, instead, focus on a single prominent person who can be used as a placeholder for a particular advancement or event in a field. Indeed, the naming of a brain area and aphasic type after Broca can be seen as an example of Stigler’s law of eponymy, which states that no scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer, and which emphasizes the perils of attributing any discovery to a single individual.

More importantly, recalling the contribution of Broca and his peers, such as Boulillard or Dax, reminds us that the 19th century is a period that saw increased interest in linking brain and psychological function through lesion studies - the anatomical-clinical correlative method. This period marks the start of a more or less continuous effort of anchoring psychology in the natural sciences by trying to understand the role of biological processes in psychological function and behavior.

The case of Monsieur Tan is an example of how, in the 19th century, the anatomical-clinical correlative method became an important tool to help scientists map psychological function onto brain structure.

(Public domain)

References

Cubelli, R., & De Bastiani, P. (2011). 150 Years after Leborgne: Why is Paul Broca so important in the history of neuropsychology? Cortex, 47 (2), 146–147. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2010.11.004

Please note that certain links to journal articles are only available within the eduroam network if they concern publications for which the university has a campus license. If you are a member of the University of Basel and want to access university resources from home, you will need to install a VPN client.

Lizenz

University of Basel