THE FOUNDATIONS OF COGNITION

3.5

Hardwired Programs

What does it mean for behavior to be instinctive? This article examines innate, fixed action patterns – hardwired programs that govern automatic, species-specific behaviors. These patterns represent a pre-cognitive mode of interacting with the environment and form the foundation for more complex behavior.1

Early organisms needed ways to act on information extracted from their environment, even in the absence of what we would consider cognition. Their behavior had to be organized and regulated to enhance their chances of survival. This directs our attention to forms of behavior that emerged early in evolution and operated without complex mental processing.

From this perspective, two central questions emerge:

How did such early forms of behavioral regulation support survival before complex cognition was available?

How, in the absence of cognition, was behavior organized at all?

For many years, a dominant explanation was that the behavior of most animals was “instinct driven.” Broadly, this term refers to innate, species-specific behavioral tendencies that emerge without prior learning or experience. A concise definition was offered by William James (1887):

«Instinct is the faculty of acting in such a way as to produce certain ends, without foresight of the ends, and without previous education in the performance.»

Crucially, this definition entails that instincts allow an organism to act without any insight or prior experience. But while the term instinct captures the general idea of innate behavioral tendencies, it remains somewhat broad and imprecise. To describe the structure of such behaviors more precisely, ethologists Konrad Lorenz and Niko Tinbergen in the 1930s–1950s introduced the concept of fixed action patterns.

Fixed action patterns are a highly stereotyped and species-specific sequence of behavior. These patterns are typically initiated by a key stimulus (or releaser) and trigger a „hard-wired program“ of action. Once released, the action pattern runs to completion. Let’s look at an actual example: The egg-rolling behaviour of the Greylag goose, as first described by Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen in their foundational ethological research. (Lorenz, 1938)

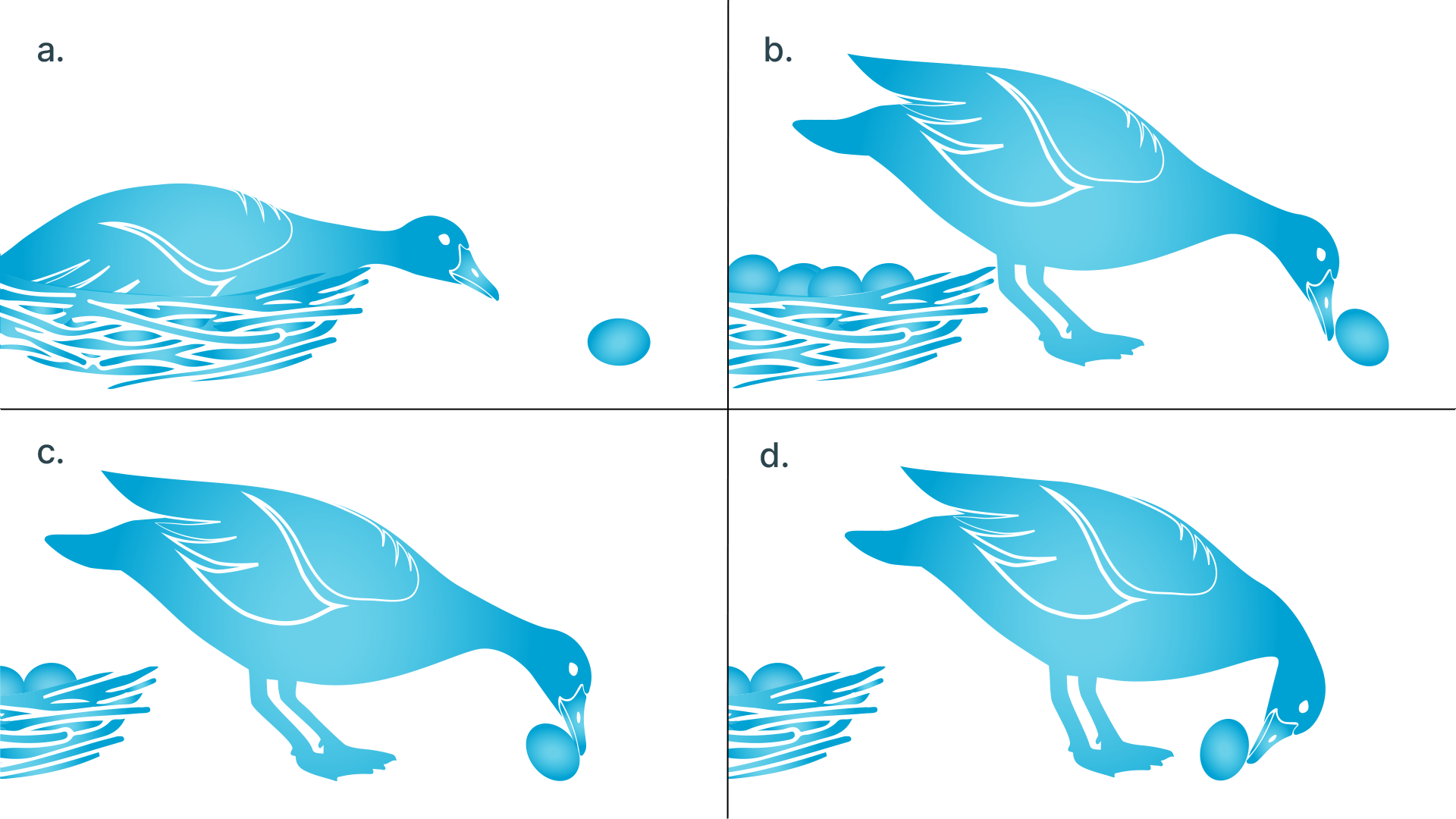

Greylag exhibiting egg-rolling instinctive behaviour:

a) it looks at the egg which has rolled out of the nest

b) it rises and tries to drag it with its beak

c) it places the underside of its beak on the top of the egg

d) it bends the neck and swings it laterally in a rhythmic movement to pull the egg back to the nest

This makes a classic example of instinctive, pre-programmed behavior–hence, a fixed action pattern, illustrating the closed-loop nature of such behaviors:

Triggered by a specific stimulus (called a releaser), and Carried out to completion once initiated, regardless of changing circumstances.

Although this behavior appears to be quite reasonable, it does not change even if the egg is removed or replaced by an artificial object.2

Karl von Frisch, 1886 – 1982

Gemeinfrei, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83416452

Konrad Lorenz 1903 – 1989

Attribution: Von Max Planck Gesellschaft (Eurobas) - Eigenes Werk

CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7311962

Konrad Lorenz (1903 – 1989) and Nikolas Tinbergen (1907 – 1988) in 1978

Attribution: Max Planck Gesellschaft

CC BY-SA 3.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons

Konrad Lorenz (1903–1989) was an Austrian zoologist and one of the founding figures of modern ethology, the study of animal behavior. Alongside Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch, he received the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for pioneering studies on animal behavior. Lorenz was critical of studying animal behavior only in laboratories. He believed that to truly understand how animals behave, we need to watch them in their natural environments, where their full range of behaviors can be observed. His method combined careful observation of animals with empathizing with them. He often used anthropomorphization (humanizing animals, see next box) to imagine their mental states.

One characteristic example of his style is found in his description of a raven’s exploratory behavior. Lorenz once remarked (cf. Bischof 2014, p. 132):

Dieses Tier will nicht fressen, sondern es will wissen, was es in dieser Gegend theoretisch alles zu fressen gibt!

This animal doesn’t want to eat – it wants to know what could theoretically be eaten in this area!

This statement reflects Lorenz’s playful flair for verbal precision, illustrating his view that animal behavior cannot always be reduced to immediate biological necessity.

Food for Thought

In many respects, other mammals may not be so different from us – or is it more accurate to say that we are not so different from them?

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human thoughts, feelings, or intentions to non-human entities – a tendency deeply rooted in our psychology. It can be a valuable starting point for thinking about the cognitive abilities of other animals, but it is also a cognitive trap that easily leads to misunderstanding. We tend to interpret animal behavior through the lens of our own mental life – assuming that when they behave like us, they think like us.

A classic example is the “guilty look” in dogs. When owners return to find a mess, their dog may display lowered ears, tucked tail, and avoidance of eye contact. It is tempting to read this as guilt, mirroring our own feelings after wrongdoing. Yet controlled experiments (e.g., Horowitz, 2009) show that dogs exhibit this posture regardless of whether they actually caused the “offense” – it is more likely a submissive response to the owner’s cues than a reflection of moral self-evaluation.

Anthropomorphism is alluring because it narrows the perceived cognitive gap between us and the world we interact with.

Have you ever apologized to an AI? We readily project human qualities onto nonhuman agents – whether other animals, machines, or even natural phenomena – seeing intention in a dog’s gaze, anger in a thunderstorm, or willful sabotage in a crashing computer.

Yet, without careful behavioral and experimental analysis, this tendency risks replacing accurate explanations with comforting human analogies.

John Tenniel’s anthropomorphic rabbit

Illustration from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Attribution: John Tenniel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Author: Fabian Müller

References

James, William. “What Is an Instinct?” Scribner’s Magazine 1 (1887): 355–365.

Lorenz, Konrad. „Taxis and instinctive behaviour pattern in egg-rolling by the Greylag goose (1938)“. Volume I, Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, 1970, pp. 316-350. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674430389.c6

Bischof, Norbert. Psychologie. Ein Grundkurs für Anspruchsvolle. Kolhammer, Stuttgart, 3. Auflage 2014

-

This chapter is partially based on Bischof, 2014 Chapter 12. (“Instinkt.” pp. 309–316). ↩

-

Watch this amusing goose video on You Tube to see the surprising variety of objects that, in the eyes of a goose, qualify as an egg. Do you remember encountering another fixed action pattern earlier in this chapter? Exactly, it was the example of the frog catching a fly. ↩