DEVELOPING THE SCRIPT

3.1

From abstract to video abstract: Know your patterns

Starting a video abstract and curious about the differences to a written abstract? If so, you first need to familiarise yourself with typical patterns that govern the audiovisual. This includes how you organise your argument.

If you primarily write academic texts, your usual approach might involve stating your main point, discussing it, and then presenting your conclusion. However, with video abstracts, it is often more effective to begin by engaging your audience and setting the context before delivering your main statement. Why is that?

Mobile phones have democratised video recording, but do not overlook the nuances of visual communication. With a century of cinematic and television history, we possess a wealth of knowledge on effective visual storytelling. This dynamic field evolves with changing conditions, including technology, society, culture, and online platforms.

Audio-visual media operate on multiple layers and follow a sequential structure. Similar to written text, they rely on audience expectations, but the challenge lies in the inability to backtrack easily if a point is not clear or if something unexpected arises. Clarity in this context requires thoughtful execution, and surprises are all the better if you as the creator have deliberately prepared them.

Video abstracts are essentially concise audio-visual arguments. They demand a clear and succinct presentation of research. Think of it as a storytelling venture, where the plot keeps your audience glued.

Our storytelling patterns are deeply rooted in cultural norms. There is no one-size-fits-all way to structure a plot. But a dramaturgical structure helps to interact with the expectations of your audience.

If you have watched blockbuster monster films, you will for instance be aware that the danger has never passed the first time the monster is killed: it will return and make its last stand – a moment you expect, but do not know when exactly it will happen, so the film keeps you anxious and on the edge of your seat. This is what plotlines and dramaturgy do: they play with your expectations, put you on high alert, surprise you and tie you to the narrative.

So let us first look at the classic dramaturgy used in Western storytelling. Arising from drama, it is divided into five acts that structure the main character’s journey through the story.

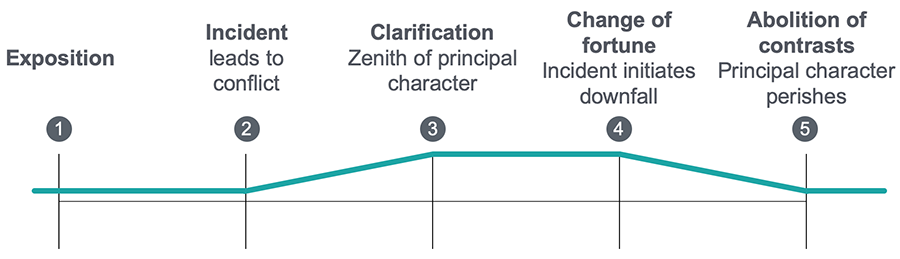

Plotline classic tragedy

In a classic tragedy, we are first introduced to the dreams and drives of the protagonist. This part is also called exposition. At the beginning of Act II, an incident leads to a conflict that challenges these dreams and with them our hero or heroine. They then address the conflict. This gives rise to hope, and in Act III the conflict seems solved in favour of the main character, with their situation much improved. Towards the end of this act, however, another incident initiates the downfall of the hero or heroine that concludes Act IV. In Act V, the conflicts are resolved in a way that is detrimental to the protagonist, a classic tragedy typically ending with their death.

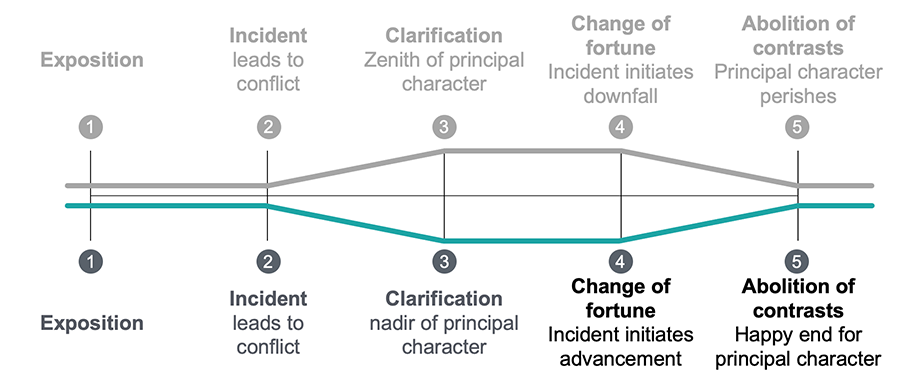

Plotline classic comedy

A classic comedy follows a mirrored plotline, with zenith and nadir of the main character inverted.

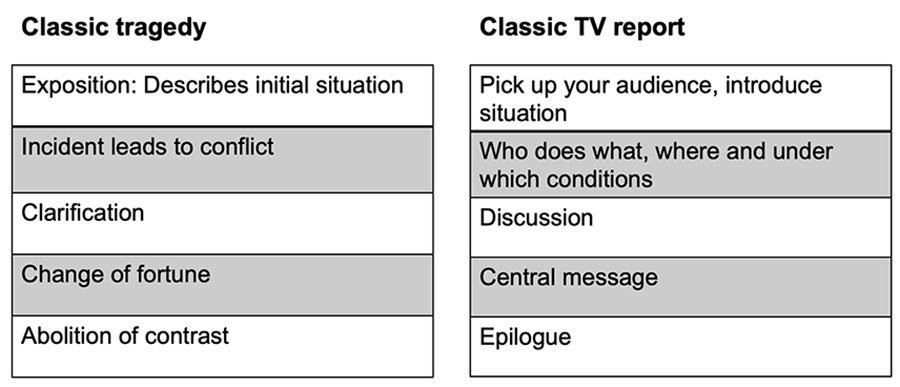

As mentioned, these plotlines have many variants and also depend heavily on genre. But consider the following schema that – many years ago – was used in the training of television journalists. It clearly links the five acts to the structure of a TV report.

Dramaturgy and argumentation

The exposition is used to involve the audience, to introduce the topic and the situation. The second part conveys basic information – usually the who, the what, the where and the when. This is how the report sets up the topical aspects of a situation, making it newsworthy at exactly the point where in tragedy we see an incident leading up to a conflict. The report follows this with a discussion of the facts; in classic drama, this corresponds to the act that initiates clarification. The change of fortune in classic drama compares to the moment in the report when the audience would expect to hear the main statement: what is the conclusion, what should the audience remember? Finally, the epilogue is the part in which the report wraps up – it gives the audience food for further thought or perhaps an outlook.

Obviously, this analogy refers to a certain age of television reports that were built on the assumption that the audience followed a sequence of broadcasted events without many possibilities to interact. Today, we see different genres on the web as well as on TV.

YouTube and series platforms, for instance, have popularised a format where the initial moments feature previews of upcoming content. This approach begins with a fundamental question: What can I showcase right away to captivate the audience and keep them engaged? Essentially, this still serves as an exposition, typically consisting of a montage of enticing statements or visuals.

In a nutshell: When you produce your video abstract, you should be aware that you are dealing with an audience that is unconsciously or consciously familiar with certain patterns. If you want to be understood quickly, you should refer to these patterns.

Further Reading

Liu, Jianxin (2019). Research Video Abstracts in the Making: A Revised Move Analysis. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication

Hyland, K. (2001). Disciplinary Discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Apply your knowledge

Before you go to the next step, reread Ava’s script.

License

University of Basel