WOMEN AND MEN IN DIFFERENT LABOUR MARKET SECTORS

3.5

Intersectionality: A tool for social justice

Historically, feminist theories have always sought to highlight the intertwining of power relations and the overlap of different forms of discrimination. It wasn’t until 1989, however, that African-American legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the concept of intersectionality in the context of a specific legal case.

The aim was to shed light on the multiple dimensions of oppression experienced by black women in a well-known US Company (Viveros Vigoya, 2016)1. Through this concept, Crenshaw intended to emphasise that black women are exposed to numerous forms of violence and discrimination based on both race and gender. At the same time, the term intersectionality would allow people to counter the tendency to treat race and gender as separate and unrelated categories of experience and analysis (Crenshaw, 1989).

In this way, intersectionality is an analytical perspective that reveals the ways in which multiple forms of inequality overlap or intersect. In other words, we can say that intersectionality is a lens for understanding reality, a concept for thinking about how the various criteria for discrimination interact.

Crenshaw describes the term as follows: “It’s basically a lens, a prism, for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other. We tend to talk about race inequality as separate from inequality based on gender, class, sexuality or immigrant status. What’s often missing is how some people are subject to all of these, and the experience is not just the sum of its parts.”2

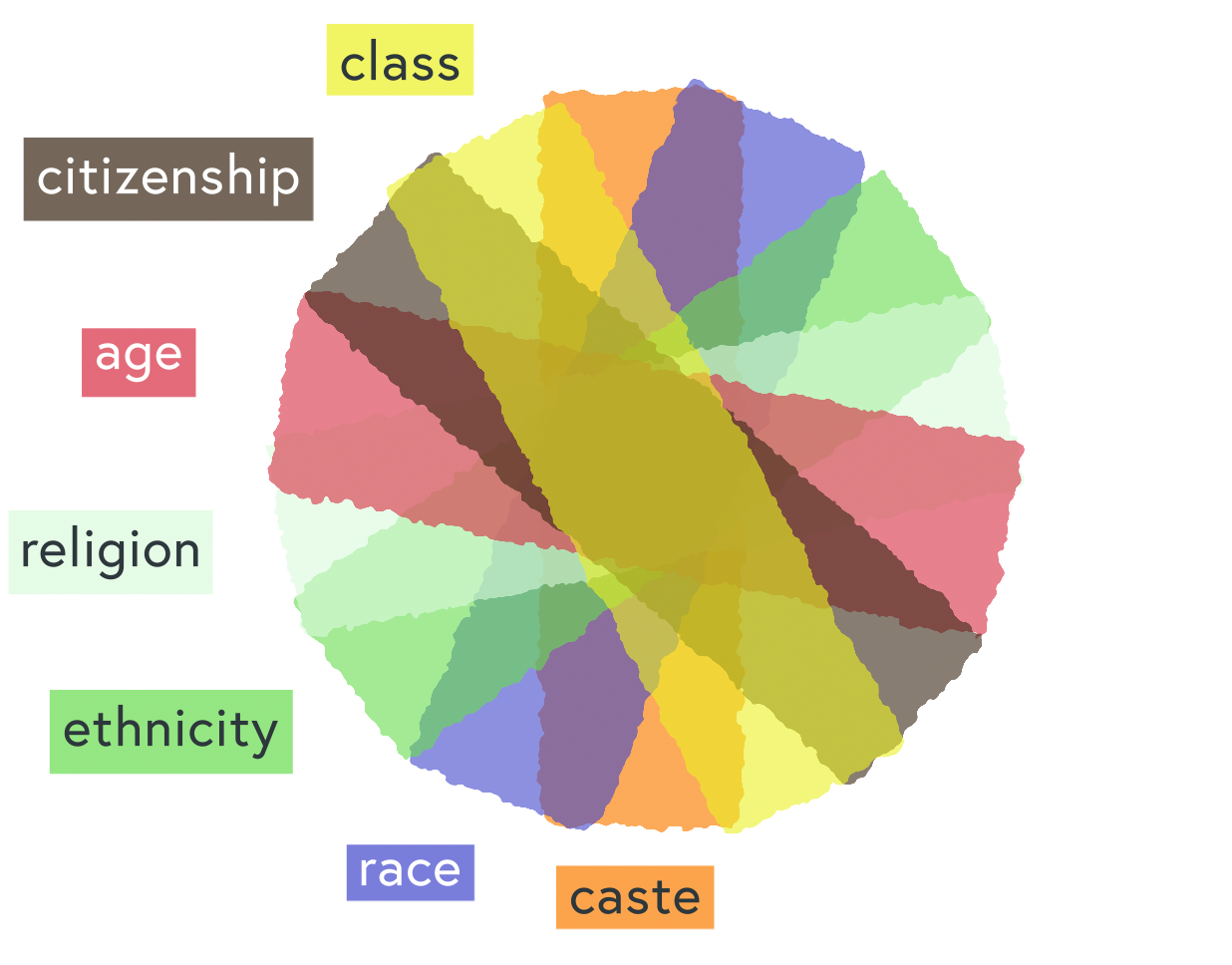

Visualisation of the intersectionality principle by Yamila Pita

Multiple actors from diverse disciplinary fields have used the intersectional approach to combat inequalities and promote social justice (Hankivsky; Jordan-Zachery, 2019). With this in mind, we must ask ourselves about the role of intersectionality when formulating and implementing public policies. If they are to become potential tools for inclusion and social change, two issues require particular attention.

Firstly, it is necessary to go beyond linear single-category thinking. Secondly, it is necessary to get rid of the biases, stereotypes, exclusions and oppressive effects present in traditional policy interventions (Hankivsky; Jordan-Zachery, 2019). Public policy instruments have to acknowledge the complexity of social structures and of the interlocking of multiple categories (such as class, race, ethnicity, caste, gender, sexuality, geographic location, migration status, religion, disability) that are embedded in prevailing power structures and relations.

While there are many challenges and obstacles3 to the use and applicability of the intersectional perspective in public policy processes, there are also many benefits to such an approach. As Hankivsky and Jordan-Zachery (2019) argue, the intersectional perspective (again, as a lens through which to understand reality) encourages a new way of looking at all aspects and stages of the public policy cycle. It also has the potential to generate new knowledge better suited to reflect and respond to people’s experiences and issues.

It is only by recognising and understanding people’s social location that public policies can contribute to the well-being of society, and particularly of marginalised groups (Manuel, 2006). Furthermore, and with the horizon of social justice in mind, it is necessary to go beyond the easily identifiable inequalities and analyse the intersection of multiple disadvantages (Hankivsky; Jordan-Zachery, 2019). These are often ignored, making those at the margins even more vulnerable.

Do you think that the intersectional approach is suitable to address the multiple dimensions of inequality? Do you know of examples of public policy designed from an intersectional perspective?

We invite you to search for a few examples.

References

Crenshaw, Kimberlé W. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1989: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available from: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Hankivsky, Olena; Jordan-Zachary, Julia S. (2019). Introduction: Bringing Intersectionality to Public Policy. In: Hankivsky, O. and Jordan-Zachary, J.S. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Intersectionality in Public Policy. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

-

Viveros Vigoya, Mara (2016). La interseccionalidad: una aproximación situada a la dominación. Debate Feminista. Vol. 52, pp. 1-17. ↩

-

Steinmetz, Katy (February 20, 2020). She Coined the Term “Intersectionality” Over 30 Years Ago. Here’s What It Means to Her Today. Time. https://time.com/5786710/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality/ ↩

-

For more on this topic, see for example: Manuel, Tiffany (2006). Envisioning the Possibilities for a Good Life: Exploring the Public Policy Implications of Intersectionality Theory. Journal of Women, Politics and Policy. Vol. 28, No. 3/4, pp. 173-203. ↩

Downloads