RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND THEORIES

1.2

How to find theories and hypothesis

Psychological theories are one way to derive possible answers to your research question. In order to do so, you need to derive both the plausible and less plausible answers to your research question in a systematic, structured way (just saying ‘answer A could be true, or answer B could be wrong’ is not enough). This tutorial helps you to navigate psychological theories.

First of all, you should look for theories that make predictions for your questions. You can also look for data that helps you predict answers. (If you look for empirical data, write down how you searched for this data.)

What are theories?

Theories give different possible answers to your research question before gathering data. (To find a clear research question see 1.1. What is a good research question?.) A theory is ‘a supposition or a system of ideas intended to explain something, especially one based on general principles independent of the thing to be explained.’1 Remember: good science aims at reliable and reproducible general statements (i.e. theories) about a particular aspects of reality that are as universal as possible.

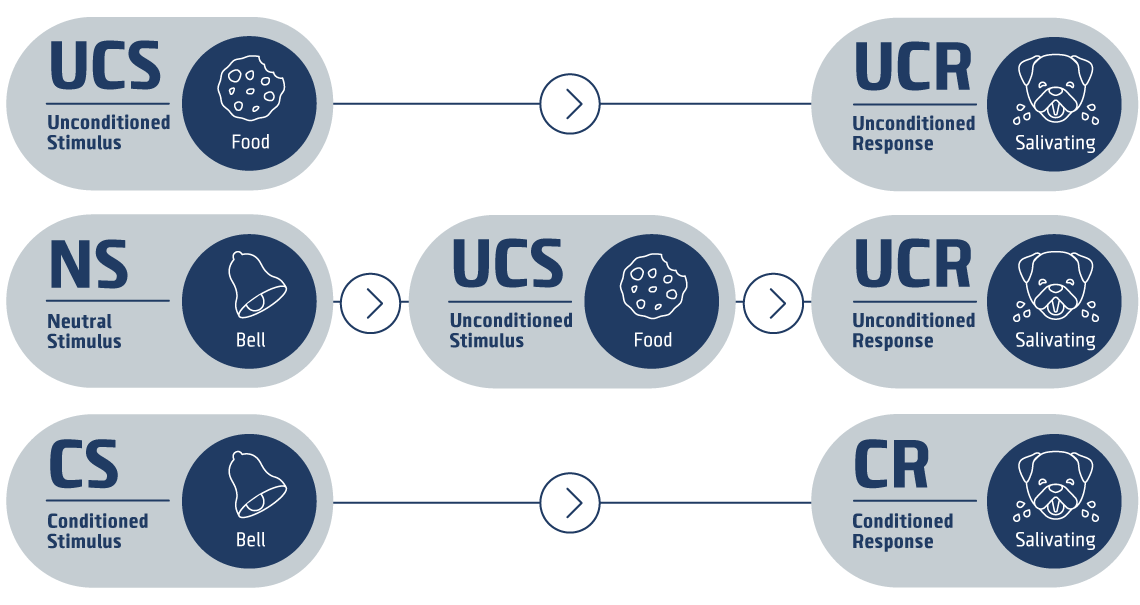

For example, Pavlov investigated how individuals learn physiological reactions to the world. He always rang a bell when he was feeding his dogs. He observed that, after a while, the dogs started to salivate when the bell rang, without even seeing or smelling food. The figure below shows Pavlov’s resulting theory – the more general rules – of how individuals learn such physiological or other responses: the theory of Classical Conditioning. Note: this theory is more abstract than Pavlov’s observations. According to the theory of Classical Conditioning individuals will, after they experienced something that causes a physiological reaction together with something neutral (that by itself causes no reaction), substitute the original stimulus with the neutral stimulus and then the neutral stimulus will elicit a physiological reaction.

This abstract theory can be applied not only to food, but to all sorts of learning situations! So, the theory helps to make predictions – before we have even conducted an experiment – about how people learn to dislike food or get addicted to substances or various other areas.

1. To find a suitable theorie you can have a look into psychology handbooks (e.g., ‘The Cambridge Handbook of …’, ‘Wiley Handbook of …’) or standard textbooks. Check if they contain chapters related to your topic and look for theories. Important: in the end you have to read and reference the original article with the theory, not a handbook or textbook!

2. You can also directly find scientific articles on your topic.

a) Read summary papers (called ‘reviews’ or ‘meta analyses’) where you will find several theories, clustered by specific criteria, with a different view on a topic. Use ‘review’ or ‘meta-analysis’ as search keywords. Some of the important journals that publish reviews or meta-analyses are Psychological Bulletin, Psychological Review and Review of General Psychology. If there is no review article on your topic, do not worry.

b) Read empirical research articles. Good news: there is no need to read every article completely, because according to APA style, theories and hypothesis are part of the introduction. You will usually find relevant theories at the beginning of the introduction or after the research question and literature review. Sometimes, there is an explicit theory section which might be called ‘model’, particularly in more formal papers, or ‘conceptual framework’. Careful: do not just look for the word ‘theory’. For example, a memory theory may be called memory model, memory viewpoint, memory position, memory approach, and so on.

Some articles do not contain explicit theories or frameworks, rather they contain just a literature review. That’s actually good: you can read the literature review closely to find the hypothesis that will be tested in the paper. Check the literature review carefully: it will refer to other published articles which can contain other theories. It is always good to search for these articles as well and read them properly.

There is usually more than one theory for a research question, so you should always try to find further theoretical literature on your question of interest.

What to do after you have found theories?

Write down what the theory predicts for your research question. Important: never mention a theory without the author, always write the name plus the author, e.g. ‘Query Theory’ (Johnson, Häubl, & Keinan; 2007). Sometimes there is no real name for a theory. In that case mention the author and come up with a good describing name by yourself.

Write down the prediction of the theories for your research question. Think through what you should observe (what participants would do), given that the theory you have found was actually true (even if you personally think this is not how people will do it). Note: in general one empirical test of a theory is not enough to falsify it, researchers test theories in various ways and derive plenty of empirical testable hypothesis from them.

What if you cannot find theories related to your research question?

First of all: ask your supervisors, they may have ideas where to find related works. While it is a good scientific practice to derive hypotheses from theoretical considerations and thus make the underlying assumptions and logic transparent and clear, it does not necessarily have to be the case that hypothesis are the result from theoretical considerations. In fact, it does not matter where you get your hypothesis from, as long as you can show how they relate (or oppose) to existing theories. But if you have no theory, you have to argue harder to justify your hypothesis and face more critical suspicion.

Nevertheless, most of fundamental scientific change started with a hypothesis not grounded in the current accepted theoretical framework. But they formed the foundation for better explanation, as the empirical evidence grew in their favor. This brings us to another important point on theories: even though their claims might sound universally true they might not exist forever.

What is a good theory?

1. Good theories target narrow questions.

Pavlov, for instance, answered the question of how individuals learn positive emotions for something neutral through experience.

2. Good theories ignore parts of the reality.

Pavlov’s classical conditioning ignored that the first experiment was about food and a bell, but spoke about learning in more general terms.

3. Theories clearly state their assumptions and principles they use. In plus, they avoids ambiguity and unnecessary assumptions.

Pavlov stated that he assumed ‘frequent presentation of neutral and positive stimulus’.

4. Theories should NOT say: due to X there will be X.

Pavlov’s theory did not assume what it explains, rather it made a new prediction.

5. Theories are always empirically grounded and they have to be falsifiable with an empirical test.

Pavlov’s classical conditioning is falsifiable because it makes predictions that we can test with experiments.

One comment regarding the last point: A statement that is always true, like ‘tomorrow it will rain or not’, is not useful. While it is an empirical testable statement, it is not useful in making predictions about tomorrow’s weather. The same holds for theories on the upcoming hair trend among livings in the intergalaxy 49. While for sure such a theory is intellectually interesting and fun, there is no way, yet, how one can test such a theory empirically. Therefore, it must remain speculative and of limited use for the knowledge of mankind. While this might sound like a harsh statement, consider that there are potentially many theories on the new hair trend among livings in the intergalaxy 49. How should we discriminate between them? How should we filter the most valid explanations? First, one can eliminate all logical inconsistent theories. Second, one might try to find plausibility criteria and thus eliminate another bunch of theories. However, we will still end up with a plethora of alternative and competing theories, all with different implications. The only way is an empirical test, which theory fails to explain more often the empirical world.

1 Oxford Dictionary, accessed September 10th, 2017.

References

Blackburn, S. (2005). The Oxford dictionary of philosophy. OUP Oxford.

Online Sources:

Oxford Dictionary: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/theory, accessed September 10th, 2017.

Lizenz

University of Basel