WHAT IS LONELINESS?

3.5

Different perspectives on loneliness 2

Sociology

Sociologists offer a different perspective than philosophers, seeing loneliness not as a timeless state of the human condition but as a salient byproduct of modernization.

They argue that the rise of industrialism, capitalism and urbanization – beginning around the early 19th century – eroded traditional forms of community and social connection, fundamentally altering how individuals relate to one another.

Early sociologists like Émile Durkheim (2006 [1897])1 introduced the concept of anomie – a pervasive sense of social disconnection resulting from the breakdown of social bonds, such as those within family and religious communities, and the increasing complexity of the division of labor. While individuals gained greater personal independence, this often came at the expense of deeper, more stable relationships. Ulrich Beck and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim (2002)2 describe this ambivalent condition as ‘precarious freedom’, highlighting the tension between newfound autonomy and the experience of social fragmentation and disconnect.

Émile Durkheim, The Division of Labour in Society

These societal shifts were both mirrored and accelerated by demographic changes and transformations in everyday life. Declining marriage and fertility rates, the rise of single-person households and fewer multigenerational living arrangements have all contributed to growing social isolation. At the same time, the decline of communal institutions – such as churches, labor unions, sports clubs and neighborhood associations – has diminished the structured social spaces that once held communities together. Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone (2000)3 prominently argued that these changes have left people more disconnected from one another than ever before, weakening the fabric of social life, and, with it, civic engagement and democratic participation.

Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone

The advent of digital technology and social media has further complicated these dynamics. While online platforms enable constant interaction, they are often criticized for fostering networked individualism – increasing the quantity of connections while reducing the depth and quality of social relationships, effectively producing lonely lives at scale. We live in a world of unprecedented connectivity and accessibility, unimaginable to previous generations, yet the more connected we become, the lonelier we seem to feel.

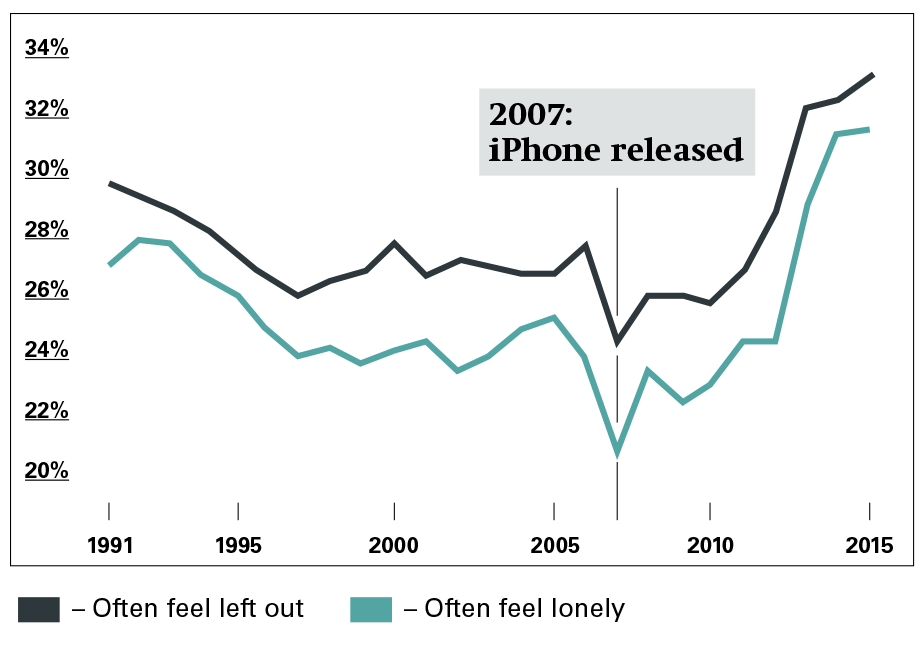

Chart from “The Atlantic”; Sept. 2017 issue (reproduced from the Monitoring the Future survey):

More Likely to Feel Lonely

Percentage of 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-graders who agree or mostly agree with the statement „I often feel left out of things” or „A lot of times I feel lonely”

Your Perspective

In a world where much of our interaction – including this very course – happens online, do you think digital platforms foster connection, or do they risk deepening our sense of disconnection?

Reflect on a moment when online interaction left you feeling more connected, and another when it left you lonelier.

Take some notes in your learning diary.

Author: Michael Stasik

-

Durkheim, Émil. 2006 (1897). Suicide. Routledge ↩

-

Beck, Ulrich and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim. 2001. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and its Social and Political Consequences. London: Sage. ↩

-

Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster. ↩