WHAT IS "AFRO-ATLANTIC"

5.4

Here and there

How do artists and writers express belonging to more than one place at once? This article explores how Afro-Atlantic creators draw on spiritual, poetic, and visual traditions to maintain connections to African heritage — offering powerful expressions of what it means to live “here and there.”

Being here and there, how does one engage with multiple places simultaneously? Unsurprisingly, the cultural outputs of Afro-Atlantic communities prominently emphasize religiosity and allusions to the African continent, which further underscores that Afro-Atlantic creative expressions are deeply rooted in their spirituality. These expressions frequently highlight their connections to African heritage and imagery, which can be interpreted as reflections of the conditions of ‘here and there.’

Example 1: “Axés do Sangue E Da Esperança”, Abdias do Nascimento

We will begin by analyzing two stanzas from a poem Axés do Sangue E Da Esperança by Abdias do Nascimento (1914-2011), a scholar and activist who embraced various roles as a poet, actor, writer, playwright, and visual artist.

Sombrio corre o sangue derramado

No mar-aquém de tanta luta devotado

Mas o sangue continua rubro a ferver

Inspirado nos Orixá que nos faz crescer

Crescer na esperança do aquém e do além

Do continente e da pele de alguém

Lutar é crescer no além e no aquém

Afirmando a liberdade da raça amém

Rio de Janeiro, 14 de março de 1982

(In: Axés do sangue e da esperança, p. 83)

Translation:

Dark runs the spilled blood,

Devoted to struggle on this side of the sea.

Yet the blood remains red, still boiling,

Inspired by the Orixás, who make us grow.

To grow in the hope of the here and the beyond,

Of the continent and the skin of someone.

To fight is to grow in the beyond and the here,

Affirming the freedom of the race – amen.

Nascimento reassesses in the poem Axés do Sangue E Da Esperança Afro-Brazilian experience, envisioning a release from the stereotypes that have persisted since the Middle Passage. By reinterpreting the narrative surrounding African-derived religious traditions in Brazil, he creates a “here and there” dynamic that fosters a connection with the spirit beings known as Orixás.

The strength of this poem lies in its vibrant commentary and creative portrayal of a pivotal diasporic event, characterized by a tragic tone yet infused with symbolic hope. Nascimento’s work highlights the spiritual importance of African deities, often framed through a political and cultural perspective that deepens the understanding of the diverse African influences in Brazilian art. He emphasizes that “African spirituality provides a perspective on life and nature that resonates profoundly with our inner emotional world.”

Example 2: Movement Saint-Soleil

In visual art, we see references to African Heritage amongst the artists of Movement Saint-Soleil in Haiti. This movement, lauded as Haiti’s inaugural “rural arts community”, was founded in 1973 by Jean Claude Garoute, affectionately known as “Tiga,” alongside Maud Robart in Soisson-la-Montagne.

The aim behind Saint-Soleil was to establish a collaborative workshop that involved local inhabitants, prioritizing instinctual creativity over conventional academic approaches. This dynamic environment often features the artwork of Saint Fleurant1, which highlights maternal themes, portraying women, children, trees, wildlife, and aspects of Haitian Vodou. Her art is distinguished by vibrant colors and animated expressions, providing a distinctive female viewpoint on the Saint Soleil movement and the wider realm of Haitian Vodou art.

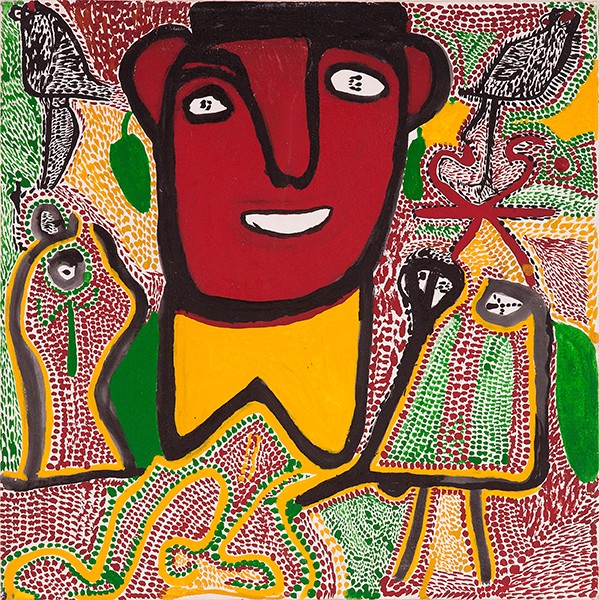

Richard Antilhomme, a dedicated Vodou practitioner from Petit Trou de Nippes, embarked on his painting journey at the age of fifty after receiving an invitation to join the Movement Saint-Soleil art circle. Malraux regards him as one of the most exceptional artists. His artwork serves as a reflection of his spiritual beliefs, intricately depicting Vodou lwas and their associated symbols.

“Loa jaden” / “Geist des Gartens”, Antilhomme Richard, Haiti, before 1999, 33.3 x 33.2 cms, collection Heinrich and Marlyse Thommen-Strasser, donation 2019, IVc 27001 © Museum der Kulturen Basel, Foto: Thomas Kern, 2013

The artwork illustrates a spirit associated with the Vodou religious tradition, which has its origins in Africa and is actively practised in Haiti. Loas (or Lwas) are spirits that act as intermediaries connecting humans with the supreme creator deity. Followers of Vodou believe in the existence of over a thousand lwa who facilitate communication between the spiritual and physical worlds. This adds another layer to the concept of ‘here and there.’

“C`est donc par le vadou que nous approcherions le mieux de leur processus de création. A l’extrême, le peintre peint parce quìl est chevauché, et paint ce que veut le loa”.2

A “here and there” signifies the outcome of diasporic awareness, kindled by a keen awareness of diverse inspirations and identities, expressed through a variety of creative forms.

Author: Zainabu Jallo

References

Do Nascimento, A. (1983). Axés do Sangue e da Esperança: Orikis. Rio de Janeiro: Achiamé/Rioarte.

Jallo, Z. (2023). Art as Medium. In U. Regehr, R. Vuille, Museum der Kulturen Basel (Eds.), Alive. More than human worlds. Hatje Cantz.

Jallo, Z. (2025). Dialectics of a Rooted Diaspora. In Z. Jallo, Diasporic Consciousness in the Material Culture of Brazilian Candomblé (pp. 133-152). Routledge.

Malraux, A. (1960). The Metamorphosis of the Gods. Translated by Stuart Gilbert. Doubleday.

-

See for instance https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louisiane_Saint_Fleurant for more information. ↩

-

[i]n the final analysis, the painter paints because he or she is ‘mounted’ (possessed) and paints what the loa wants”. English translation by Stuart Gilbert ↩