MEMORY DEFICITS

4.3

Amnesia

What types of amnesia exist, and what can cause amnesia? Read this article by Dominique de Quervain.

Amnesia is defined as a condition with disturbed memory functions.

Depending on whether the disturbance affects the recollection of past experiences or the formation of new memories the amnesia can be:

- retrograde, i.e., when information from the past cannot be retrieved, or

- anterograde, i.e., when new information cannot be stored.

Depending on whether the disturbance is temporally restricted or permanent, the amnesia can be:

- reversible, i.e., the amnesia is temporally restricted, or

- irreversible, i.e., the amnesia is permanent.

The features retrograde/anterograde and reversible/irreversible occur in all four combinations. Here are examples of each:

- Reversible retrograde amnesia: impaired information retrieval caused by acute elevation of cortisol levels.

- Irreversible retrograde amnesia: loss of stored information due to a lesion of the hippocampus.

- Reversible anterograde amnesia: inability to store new information due to the influence of large quantities of benzodiazepines (e.g. diazepam) or alcohol.

- Irreversible anterograde amnesia: inability to store new information due to a lesion of the hippocampus.

Some brain disorders can cause both anterograde and retrograde amnesia. In this case, we call it global amnesia. This can occur after a severe brain injury or in an advanced stage of dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

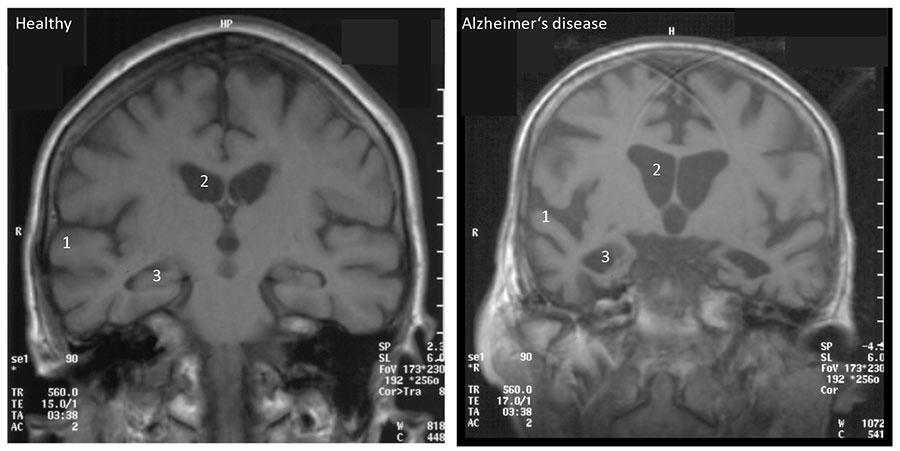

In Alzheimer’s disease, nerve cells are increasingly disturbed in their function and eventually die. This process typically begins in brain regions related to memory, including the hippocampus, and gradually spreads across the entire brain (see Figure 1, Alzheimer’s disease). It should be noted that the disease may cause noticeable memory problems in its early stages without showing abnormalities in the MRI.

Figure 1: Brain changes in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. On the left, you can see an MRI of a 75-year-old healthy person with a normal-sized neocortex (1), normal-sized ventricles (2), and a normal-sized hippocampus (3). On the right, you can see an MRI of a 75-year-old patient with advanced Alzheimer’s disease, showing shrinkage of the neocortex (1), enlarged ventricles (2) due to loss of brain volume, and massive shrinkage of the hippocampus (3). Copyright: Dominique de Quervain.

Learn more about Alzheimer’s disease and memory deficits in general in the book chapter recommended below. You’ll find a PDF of the chapter on ADAM.

References

Cognitive Neuroscience: The Biology of the Mind; 5th Edition. Michael Gazzaniga, Richard B. Ivry, George R. Mangun; Page 382 (including “9.2 Memory Deficits: Amnesia”) – 384 (excluding “9.3 Mechanisms of Memory”).

Lizenz

University of Basel