MASKING

4.5

Iconoclasm

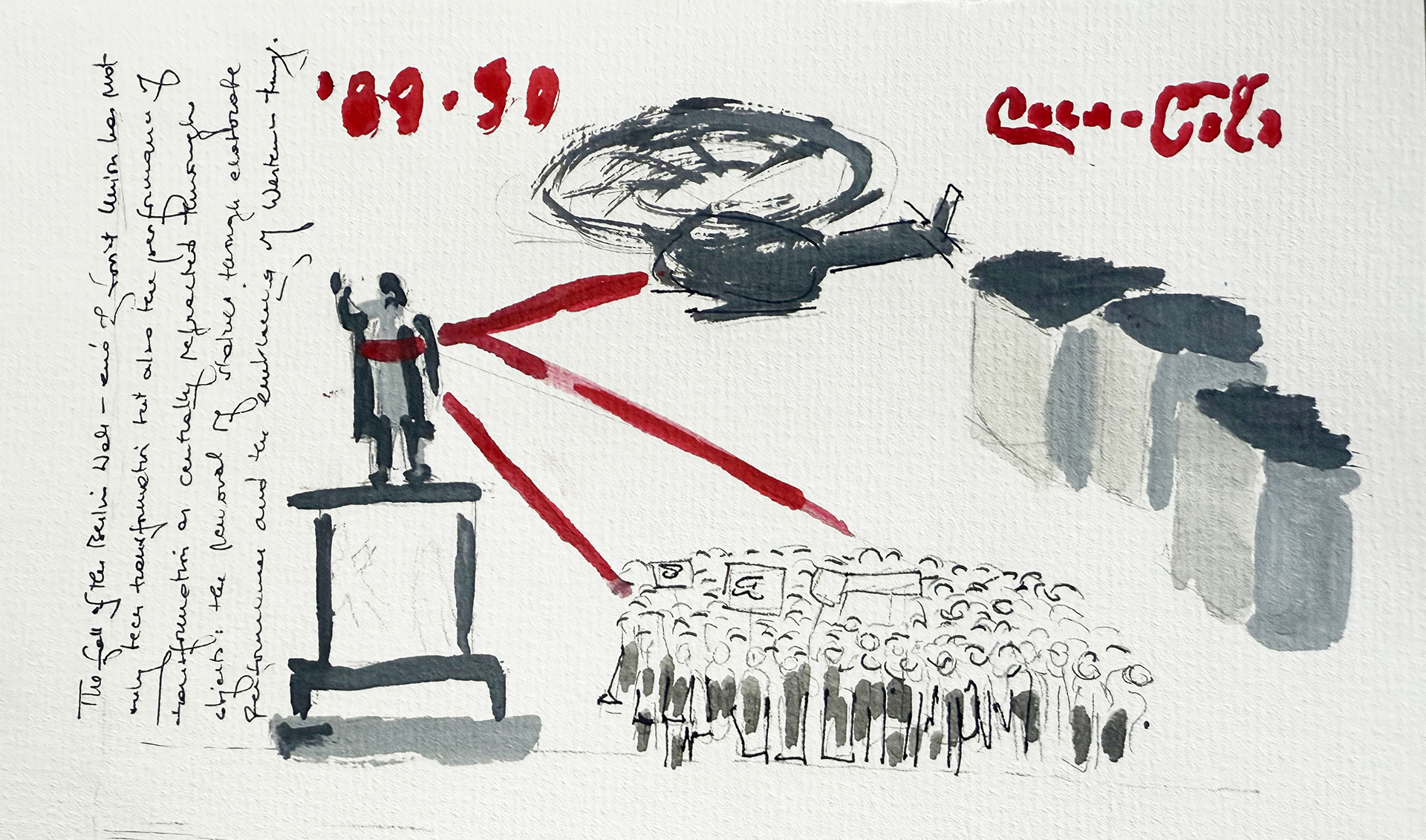

Field drawing by George-Paul Meiu

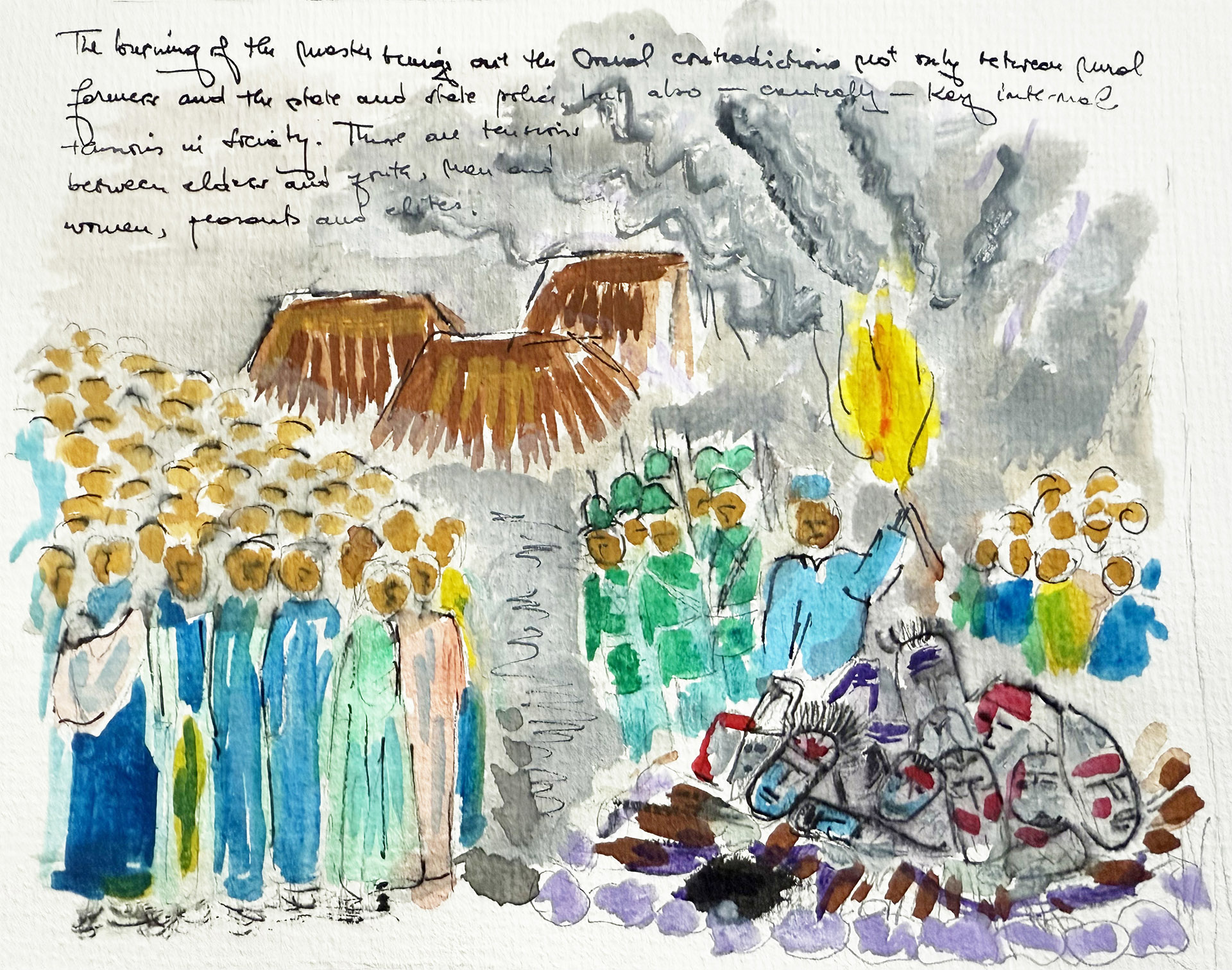

Field drawing by George-Paul Meiu

Iconoclasm = the process of performative refutation or destruction of objects associated with broader political, religious and cultural orientations. These can include masks, status, icons, and other material symbols.

The instauration of new political regimes has often been accompanied by efforts to expose and demonise the masks of the previous regimes. This process can unfold metaphorically in the sense of “unmasking” so-called traitors, spies, or collaborators, revealing the secret mechanisms that sustained the previous regime.

But it can also play out in more tangible ways. New powers can often be uneasy with the physical artifacts of the past, including actual masks, statues, icons, and symbols that were either employed or tolerated by the former regime. This process is often referred to as iconoclasm, and it has been an integral part of the rituals of state-making in colonial and decolonial, socialist and postsocialist contexts.

Field drawing by George-Paul Meiu

Field drawing by George-Paul Meiu

Following independence in 1958, for example, the West African state of Guinea undertook major campaigns to eradicate the kinds of traditional masks that, during the colonial regime, had figured as signs of a supposed African “backwardness” or “lack of civilization”.

As anthropologist Mike McGovern shows in his book Unmasking the State, this process – informed by elite desires to overcome colonial legacies – was complicated by a similar condescension towards practitioners of African religions:

“In this way, iconoclasm can be understood as making a claim for equal membership in a world of nations. Newly independent countries like Guinea knew themselves to be denigrated by the others, including the erstwhile colonizers. Iconoclasm provided a solution to the desire to eradicate the embarrassing residue of premodern backwardness from the body politic. Sékou Touré [the country’s new president] made frequent calls for Guineans to ‘come back to themselves,’ to reclaim an authentic precolonial self that had been terribly deformed by the experience of colonialism. Despite this he partook in the often anxious undertaking of eliminating embarrassing traces of precolonial backwardness. Those who practiced African religions in Guinea were not embarrassed by their alleged barbarity … only the modernist iconoclasts seem to have been fully convinced of the peasants’ belief.” (McGovern, Unmasking the State, 19-20)

From an anthropological perspective, masks and acts of unmasking offer a lens into the symbolic and material process of regime change. Far from neutral objects, masks become sites of ideological contestation. As in Guinea, attempts to discard them often reinscribe colonial logics, showing that unmasking the past can obscure as much as it reveals, reproducing power along similar lines even as it claims to dismantle it.

Your Perspective

- How do symbolic acts like the removal or destruction of masks, statues, or icons function as tools of political legitimacy in the formation of new regimes?

- In what ways can efforts to reject colonial legacies end up reproducing the same hierarchies or ideologies they aim to dismantle?

Author: George-Paul Meiu

Reference

McGovern, M. (2012). Unmasking the State: Making Guinea Modern. University of Chicago Press, pp. 19-20.