NON-DECLARATIVE MEMORY

6.3

Extinction

What is extinction and why is it important? Read this article by Dominique de Quervain.

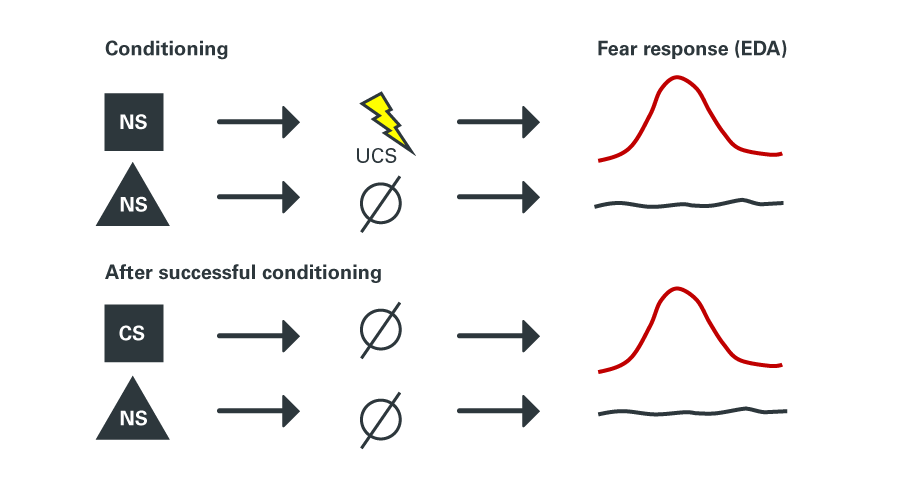

The term extinction is used in the context of conditioning and refers to the phenomenon where a non-reinforced conditioned response fades over time. Take this classical conditioning experiment as an example: in a study in healthy volunteers you first pair a geometrical shape with a light electric shock (this study needs ethical approval and good colleagues). After successful conditioning, you repeatedly show the shape (initially causing a fear response) without pairing it with a shock. As a result, your probands exhibit fewer and fewer fear responses until the conditioned response fades completely. The conditioned stimulus has been extinguished (see Figure 1 A and B).

Figure 1 A: Classical conditioning. An electric shock is an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) that leads to a fear response. Fear leads to increased sweating that can be measured with electrodermal activity (EDA). During conditioning, a neutral stimulus (NS) – a square in this example – is repeatedly paired with the UCS, turning it into a conditioned stimulus (CS). After successful conditioning, the CS alone leads to a fear response. Another neutral stimulus (triangle), which has never been paired with the UCS, does not lead to a fear response. Copyright: Dominique de Quervain.

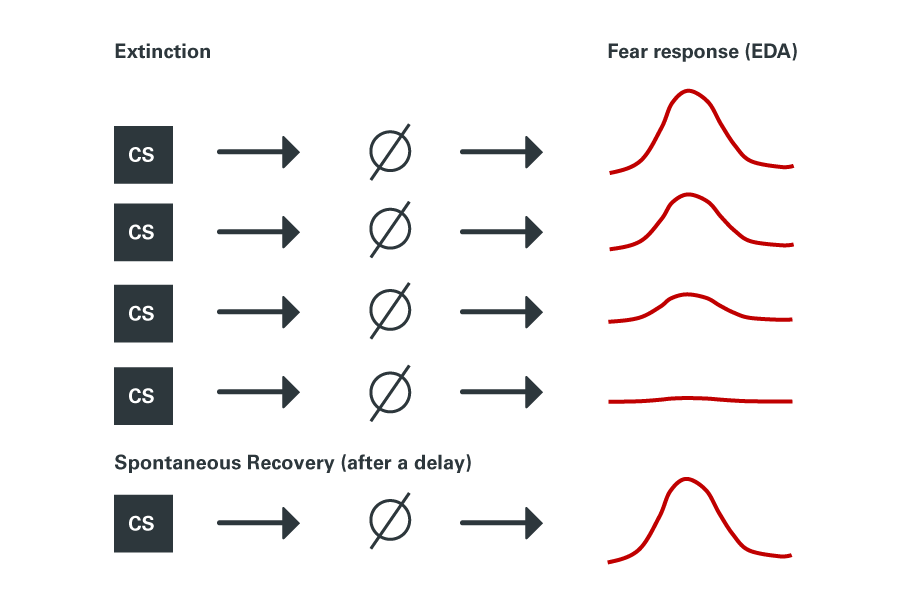

Figure 1 B: Extinction. During extinction, the CS is repeatedly shown without the electric shock. This leads to a weaker and weaker fear response until it disappears completely. After a delay (weeks to several months), and without any intervention, the fear response may reappear when the CS is shown, a phenomenon called spontaneous recovery. Copyright: Dominique de Quervain.

What are the mechanisms of extinction? One explanation is that the original association is simply unlearned or forgotten. However, a phenomenon that occurs after successful extinction requires an alternative explanation: if you invite your probands to return after a couple of months, and you show them the shape, they exhibit again a fear response. This means that the original association built during classical conditioning has not been erased. So the alternative explanation for extinction involves new learning (the shape-no shock association), which competes with the original association (shape-shock). After successful extinction, the newly formed extinction memory (shape-no shock) dominates, but a couple of months later, the original association prevails again (see Figure 1 B).

That’s why extinction is mostly seen as a process involving the generation of new memory (“extinction memory”), and as such, it is an associative non-declarative type of memory.

Extinction is believed to be the process that underlies exposure-based psychotherapy. Let’s take a patient with a fear of spiders as an example. During therapy, the patient is gradually exposed to a real spider and instructed not to run away, which would be their usual response. The patient then learns that nothing bad happens when the spider is present, and an extinction memory is formed, storing this new association (spider-nothing bad happens). This newly formed extinction memory competes with the original fear memory. After successfully completing therapy, the patient’s fear of spiders has been alleviated, but it returns after a couple of months, indicating that the original fear memory is still there and is stronger than the extinction memory over time. The return of fear after an initially successful psychotherapy is often observed, so it could be helpful if the extinction memory could be strengthened pharmacologically. Read more about this approach in the next chapter.

Could fear memories be permanently removed? Studies in animals have shown that once memory is reactivated (by retrieval), it enters a labile state that needs reconsolidation to be conserved. If the process of reconsolidation is pharmacologically disturbed, then the memory is permanently lost. This approach is currently being tested in humans, but it is still too early to determine its potential.

License

University of Basel