INTRODUCTION

1.3

The Problems with History

What is the value of learning about history? What problems are associated with historical narratives? Explore these questions in this article.

The value of History

What exactly does history teach us? Consider the following quotes:

“What’s past is prologue.” (William Shakespeare, Tempest, 1610)

“The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” (L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between, 1953)

“Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.” (Winston Churchill, 1948; likely paraphrasing George Santayana, 1905)

History may help us understand the beginnings of something (Shakespeare quote), understand how things have changed so much over time that they now seem foreign (Hartley quote), and help us avoid mistakes committed in the past (the Churchill/Santayana quote). Given the state of the world today, there is little evidence to back up any of these salutary effects of learning about history. Hope nonetheless prevails.

The problems of history

There are many problems with history and historical accounts but the following are likely central ones.

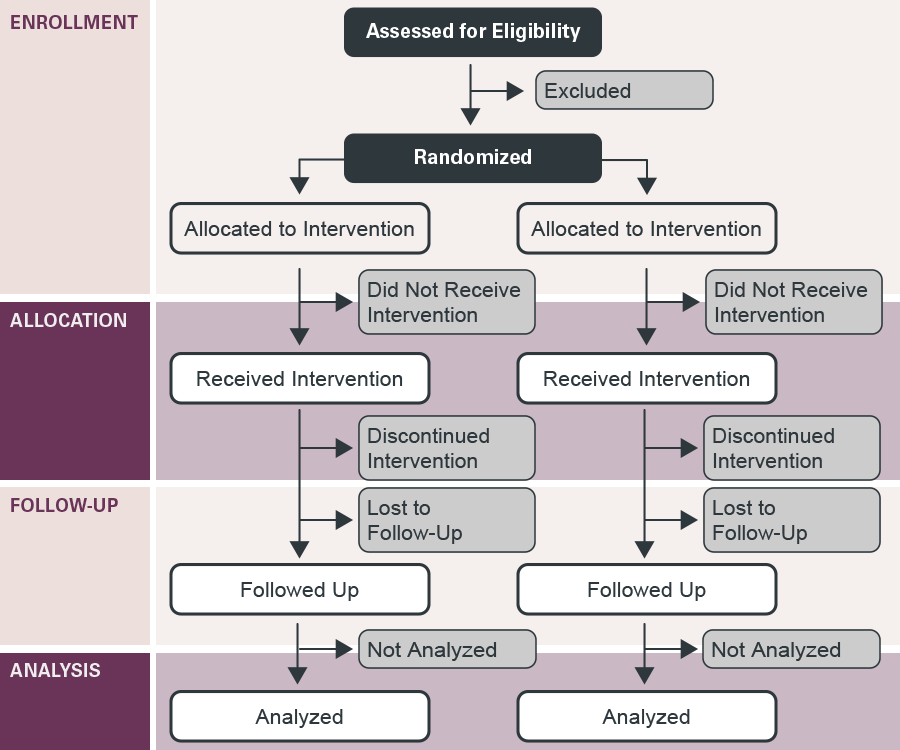

The problem of causation

Science tries to establish causation with experimentation. It uses randomization to produce counterfactuals (“what would happen if not for the specific (manipulated) factor of interest?”). The problem with history is that it offers no such counterfactuals. Historians can sometimes create counterfactuals under some specific assumptions (e.g. compare two invasions of the same army or similar invasions by different armies) but such comparisons are always imperfect because they lack perfect randomization and full comparability; the groups (e.g. armies) and situations (e.g. battles) considered can differ in many respects beyond the factor of interest. As a consequence, it is always problematic to assign causes to historical events, and historical accounts can suffer from being a “just so” story.

History is not value free

Historical accounts are often written by victors, or, not uncommonly, by losers with some ax to grind. In other words, historians (academic or otherwise) have some perspective, some point of view, and are therefore not neutral observers or interpreters of history. For example, they may fall prey to ethnocentrism and give too much attention to the contribution of the historian’s own group, or to hindsight, which refers to the tendency to interpret events based on what is already known at the time of writing. Academics need tenure, funding, and an ego caressed by reputation and accolades; these come more often from opinionated insight than descriptive neutrality. No history is value free.

The problem of lack of diversity

The latter point argues that historical accounts do not emerge in a vacuum. A corollary of this is that history is often biased and misogynistic. This is a product of inequality and misogynism in society rather than an unavoidable, deep-seated characteristic of historiographic methods. One consequence of this state of affairs, however, is that, when covering the history of a particular field, say psychology, one may end up covering a lot of material on a small set of privileged western individuals - dead white males - and very little or not at all on other social groups. Increasing the diversity and representativeness of our historical accounts is an uphill struggle. One must imagine an instructor and students happy to try. Can YOU think of ways of increasing diversity in our historical accounts?

Randomized control trials help scientists estimate causal effects by establishing counterfactuals – history provides no true randomization making it difficult (impossible?) to establish causality in historical accounts.

(CC BY-SA 3.0; Flowchart of Phases of Parallel Randomized Trial - Modified from CONSORT 2010)

License

University of Basel